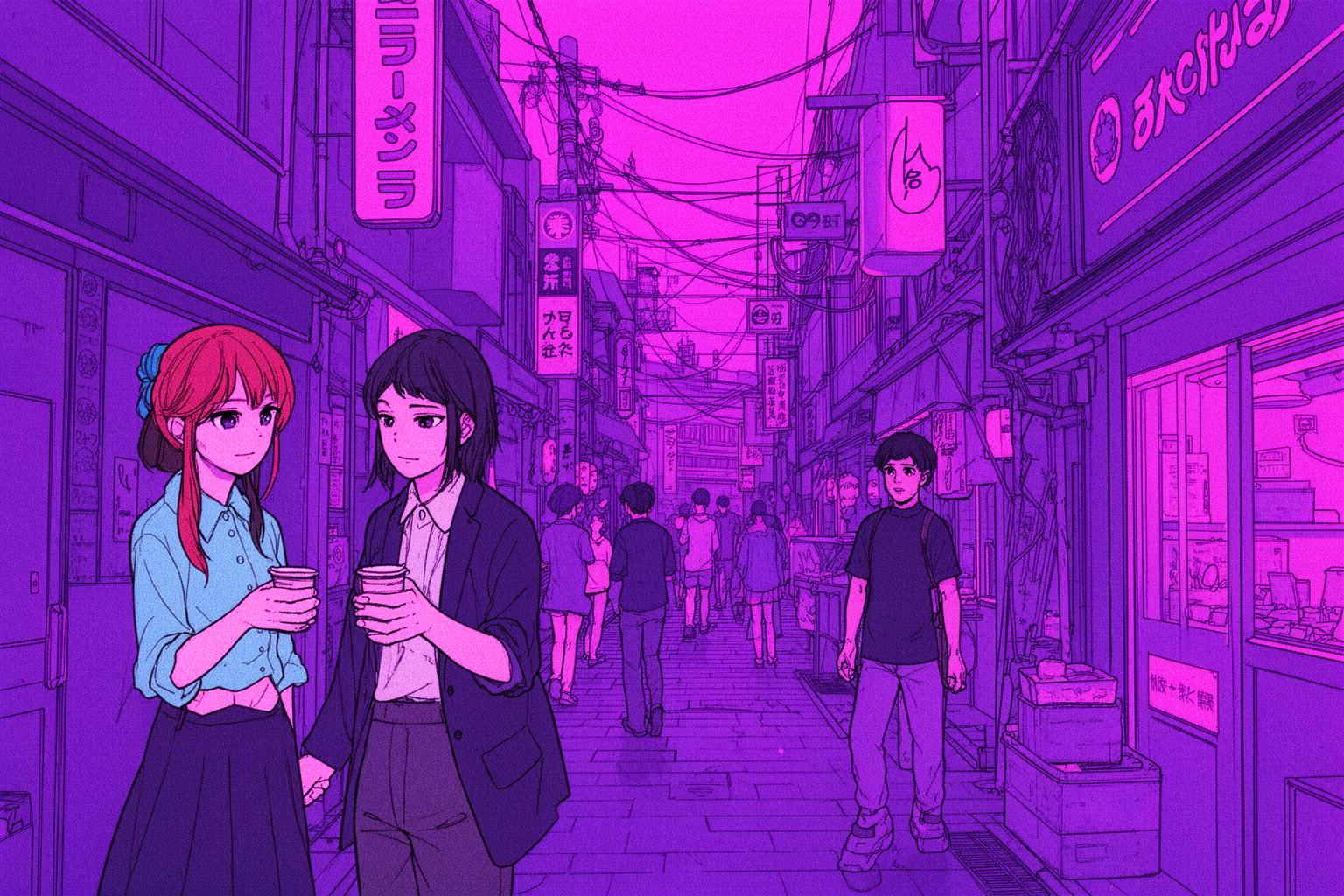

What’s good, fellow travelers and culture seekers? Keiko here, your Tokyo-based guide to all things cool and authentic in Japan. Today, we’re ditching the slick, high-tech version of Japan you see in movies. We’re logging off from the neon-drenched future and dialing it way, way back. I’m talking about a full-on time-slip experience, a journey into the heart of Japan’s Showa Era—the mid-20th century—without needing a DeLorean. We’re diving headfirst into the world of yokocho. These aren’t just back alleys; they’re living, breathing time capsules packed with tiny bars, sizzling grills, and unfiltered Japanese soul. It’s where you can sip sake next to a salaryman who’s been coming to the same spot since the 1960s, and honestly, it’s a vibe you just can’t download. Forget your curated, minimalist cafes for a second. Yokocho are the real deal—gritty, intimate, and no cap, one of the most legit cultural experiences you can have in this country. It’s where stories are swapped over cheap drinks, where the air is thick with the smoke of grilled chicken skewers and decades of laughter. It’s giving main character energy in a historical drama, and you’re invited to the show. This is Japan unfiltered, a low-key portal to its past, hiding in plain sight next to bustling train stations and gleaming skyscrapers. So, grab a seat, ’cause we’re about to spill the tea on how to navigate these magical, lantern-lit labyrinths.

For a deeper look into these nostalgic alleyways, explore our guide to Japan’s authentic Showa-era yokocho.

The OG Vibe: Cracking the Code of Showa Nostalgia

Before you casually slide onto a tiny stool and order a beer, it’s quite important to know the backstory. Yokocho aren’t just some retro theme parks made for tourists; their aesthetic is hard-earned. Understanding their history is the key to unlocking their charm, turning a simple meal into a deep cultural experience. It’s the difference between merely seeing the set and truly understanding the entire movie.

Back to the Future: The Post-War Origins of Yokocho

Let’s rewind time. The origin of most iconic yokocho lies in the grit and resilience of post-World War II Japan. Right after the war, cities were devastated and resources extremely scarce. From this necessity, black markets, or yamiichi, emerged, often near major transport hubs where people gathered. These markets were chaotic, lively, and crucial spots where you could find everything from food to daily goods that were otherwise unavailable through official means. They were essential to survival for many. As Japan gradually rebuilt, these black markets began to formalize. The makeshift stalls selling bootleg liquor and inexpensive, hearty food turned into more permanent establishments, yet they never lost that raw, bustling energy. They naturally grouped into tight clusters of small eateries and bars tucked away in narrow alleyways—the yokocho—branching off main streets. The cramped spaces weren’t a stylistic choice but a practical way to maximize limited space in a recovering city. This history is literally etched into the walls. When you see the worn wooden counters, the maze of exposed electrical wires, and buildings packed so closely they almost support each other, you’re looking directly at the descendants of those post-war yamiichi. It’s a testament to the Japanese spirit of creating something remarkable out of almost nothing.

Salaryman Sanctuary: Beyond Just a Bar

During Japan’s rapid economic growth in the 1960s and 70s—the peak of the Showa Era—the yokocho found a new role and a new regular: the salaryman. These corporate warriors were the backbone of Japan’s economic miracle, known for their legendary long hours and fierce loyalty to their companies. After a tough day at the office, the yokocho became their refuge. It was a third space, separate from the strict hierarchies of work and the duties of home life. In the soft glow of a single lantern, they could shed their corporate masks. They could grumble about their bosses, celebrate small wins, and build camaraderie with coworkers over cheap sake and grilled offal. The yokocho acted as a social pressure valve. Their small size was crucial; with only a few seats, conversation was unavoidable. You weren’t just a customer; you were part of a temporary community, sharing moments with the bar master (taisho) and strangers sitting shoulder-to-shoulder beside you. This culture endures today. Even now, you’ll see groups of coworkers relaxing, ties loosened, faces flushed from warm sake. For them, the yokocho isn’t just a drinking spot; it’s a vital ritual, offering genuine human connection in an often impersonal modern world.

The Aesthetic: A Sensory Feast

The atmosphere of a yokocho is a full-sensory experience, an overload in all the best ways. It’s something you feel as much as you see. Let’s break down that aesthetic. Visually, it’s organized chaos. The first thing you’ll spot is the iconic red lantern, or akachochin, hanging outside—a glowing beacon announcing “we’re open.” Stepping inside, your eyes adjust to the dim, warm light. The walls often display a collage of history—yellowed menus with handwritten kanji, vintage beer posters from long ago, and scribbled notes left by satisfied patrons. Space is precious. You’ll perch at a simple wooden counter, often worn smooth and sticky from decades of use, with just enough room for your plate and glass. Now, listen. The soundtrack of a yokocho is a beautiful symphony of sounds. You’ll hear the constant sizzle and pop of meat on the hot grill, the rhythmic chop of a chef’s knife on wood, the satisfying clink of glass bottles, and a steady hum of conversation and laughter filling the small space. It’s never silent, but it’s a comforting, communal hum. And the smell? It’s everything. The intoxicating, savory scent of charcoal and grilling meat—yakitori, motsuyaki—mixes with the sweet, soy-based aroma of simmering nikomi stew. There’s the faint, sweet perfume of warmed sake, and yes, often the lingering nostalgic scent of cigarette smoke, a relic of a less health-conscious era but an unmistakable part of the classic yokocho atmosphere. This sensory tapestry is what makes the experience so immersive. It’s not polished or slick; it’s real, it’s human, and utterly unforgettable.

Tokyo’s Yokocho Playbook: Iconic Alleys You Can’t Miss

Tokyo stands unrivaled as the champion of yokocho culture, boasting a maze of legendary alleys each with its own distinct character. Exploring them feels like moving between various movie sets, each narrating its own tale. One could spend a lifetime uncovering them all, but a handful of these iconic spots are absolutely essential for any first-time visitor. These venues define the genre and have been romanticized in films and literature for decades.

Shinjuku’s Double Feature: Omoide Yokocho & Golden Gai

Shinjuku Station, the world’s busiest railway hub, is a bustling whirlwind of modernity. Yet just steps from its gleaming exits, you’ll discover two of Japan’s most famous yokocho, each presenting a starkly different taste of the past. Together, they perfectly showcase the diversity within yokocho culture.

Omoide Yokocho: Memory Lane, AKA “Piss Alley”

Let’s begin with Omoide Yokocho, which translates charmingly as “Memory Lane.” However, those in the know refer to it by its more notorious nickname, “Piss Alley,” a relic from its rough post-war days when public facilities were scarce, to say the least. Fear not—it’s much cleaner now, but the name reflects its raw, unvarnished origins. Situated on Shinjuku Station’s west side, this cluster of narrow, smoke-filled alleyways feels like a 1950s movie set. The instant you pass beneath its entrance, a wall of fragrant smoke from dozens of yakitori grills envelops you. The alleys are so tight you must walk single-file, brushing past patrons perched on tiny stools spilling out from the bar fronts. The atmosphere is classic—blue-collar salaryman paradise. The specialties here are undeniably yakitori (grilled chicken skewers) and motsuyaki (grilled offal skewers). Menus are straightforward, the beer is cold, and the energy is electric. It’s loud, packed, and superbly authentic. You’ll spot chefs, their faces glowing in the coals’ light, expertly turning skewers with a practiced flick of the wrist. This is an ideal starting point for your yokocho adventure—approachable despite its gritty reputation, and visually striking. Simply put, this place is the blueprint for the quintessential yokocho experience.

Golden Gai: The Cinematic Micro-Bar Maze

A short walk away on Shinjuku’s east side lies Golden Gai, a completely different world. If Omoide Yokocho feels like a bustling food market, Golden Gai is an intimate, bohemian maze. It’s a preserved block of six tiny, interconnected alleys packed with over 200 micro-bars, some so small they seat only five or six patrons. The ramshackle, two-story wooden buildings miraculously survived both post-war redevelopment and bubble-era demolition. During the 60s and 70s, this was a hotspot for artists, writers, musicians, and filmmakers—the creative counter-culture of Tokyo. That artistic, intellectual spirit still lingers. Each bar carries a unique theme and personality, crafted by its owner, or “master.” One might be a punk rock den, another a shrine to vintage films, and a third a quiet, reflective spot for savoring rare whiskey. Golden Gai focuses less on quick, cheap meals and more on conversation and curated ambiance. Be aware that many bars charge a cover fee (otoshi), and some guard their regulars closely, sometimes displaying “no tourists” signs. Still, many welcome and enjoy chatting with foreign visitors. The key is to peek inside, absorb the vibe, and select a place that resonates. It’s a spot for slow sipping and deep conversation—a genuinely cinematic experience that feels like stumbling upon a secret society.

Shibuya’s Hidden Gem: Nonbei Yokocho (Drunkard’s Alley)

Shibuya is renowned for its Scramble Crossing—a tidal wave of people and flashing ads. It’s the heart of modern youth culture. Yet, tucked away almost humorously close to the chaos is Nonbei Yokocho, or “Drunkard’s Alley.” This tiny, tranquil lane quietly resists the surrounding ultra-modernity. Dating back to around 1950, it’s a single street lined with a couple dozen quaint, lantern-lit bars and eateries. It’s far quieter and more intimate than Shinjuku’s yokocho. Entering Nonbei Yokocho feels like uncovering a secret garden. The clamor of Shibuya fades into a soft murmur of voices and gentle glass clinks. The establishments are incredibly small, reinforcing the sense of exclusivity and discovery. It’s the perfect refuge when Shibuya’s sensory overload becomes too much. Here you’ll find excellent yakitori spots alongside tiny, specialized bars. It’s a low-key treasure most tourists, rushing to the Scramble, entirely overlook. For those aware (iykyk), it’s a precious slice of Showa-era calm amid the storm.

Ueno’s Ameyoko: The Daytime Hustle and Nighttime Glow

Ameya Yokocho, or “Ameyoko,” near Ueno Park offers a distinct yokocho experience. This isn’t merely a collection of bars; it’s a sprawling, lively open-air market with roots in the post-war black market era. By day, it’s a frenetic bazaar where vendors sell everything from fresh fish and exotic fruits to cheap clothes and cosmetics. The vibrant energy recalls its yamiichi origins. As dusk falls, Ameyoko transforms: market stalls close, and the izakaya and standing bars lining the street and side alleys spring to life. Many bars spill onto the street, with patrons seated at crude tables propped on plastic crates. The atmosphere leans less toward intimate, smoky interiors and more toward lively, open-air revelry. You can pick up fresh sashimi from a fishmonger’s stall and enjoy it right there with a cold beer. It’s an excellent spot for early evening drinking or tachinomi (standing-while-drinking) before heading to a more traditional yokocho. Gritty, diverse, and vibrant, it blends market and drinking culture in a way uniquely Tokyo.

Beyond the Capital: Yokocho Adventures Across Japan

While Tokyo may be the epicenter, the yokocho spirit thrives vibrantly throughout Japan. Exploring beyond the capital reveals regional takes on the tradition, each boasting its unique character, local specialties, and cultural nuances. It’s a wonderful way to discover how various cities embrace this cherished institution.

Osaka’s Energy: Where the Atmosphere is Louder

If Tokyo represents the refined older sibling, Osaka is the lively, loud, and unapologetically bold younger counterpart. Renowned for its kuidaore culture—meaning “eat until you drop”—Osaka’s yokocho perfectly embody this exuberant, food-loving vibe. The ambiance tends to be louder and the locals notably more openly friendly than in Tokyo, making it easier to strike up conversations with complete strangers.

Namba and Hozenji Yokocho: Cobblestones and Culinary Chaos

Namba station’s surroundings in Osaka offer a sensory overload, with yokocho at the very center of the buzz. Numerous alleys are densely packed with spots dishing out Osaka soul food such as takoyaki, okonomiyaki, and kushikatsu (deep-fried skewers). A highlight is Hozenji Yokocho, a beautifully preserved stone-paved alley near the iconic Hozenji Temple. It feels as though you’ve wandered onto a historical drama set. The narrow lane is lined with traditional eateries and bars, their lanterns casting a gentle, flickering light over the damp cobblestones. Slightly more upscale and polished than the usual gritty yokocho, it still captures that nostalgic, intimate charm. After paying homage at the temple’s moss-covered statue, stepping into one of these venues for premium sake and kappo-style dishes is a quintessential Osaka experience—a perfect blend of culinary mastery and historical ambiance.

Fukuoka’s Yatai Scene: The Open-Air Relatives of Yokocho

In Kyushu, Fukuoka presents a distinctive spin on the yokocho with its well-known yatai—open-air food stalls. Though not technically yokocho since they are not located in alleys, yatai share the same spirit: cozy, unpretentious spaces where strangers bond over simple, hearty meals. Each night, around 100 stalls line the waterfront in districts like Nakasu and Tenjin. These yatai function as mini restaurants, seating about eight to ten patrons shoulder-to-shoulder around the cooking area. The menus showcase Fukuoka favorites: Hakata ramen’s rich tonkotsu broth, hot gyoza, and assorted grilled skewers. The atmosphere is warm and communal, with the taisho (stall owner) cooking in plain sight, chatting with customers and fostering a lively, family-like environment. Moving from one yatai to another, sampling diverse dishes, is the local way to savor an evening out. This magical, transient experience ends each morning as the stalls are packed away without a trace. Yatai culture is a rare and valued treasure in Japan, with Fukuoka as its last significant bastion. It’s a must-try for anyone eager to experience authentic, community-centered dining.

The Yokocho Menu, Unlocked: What to Order to Look Like a Pro

Walking into a yokocho for the first time can feel intimidating, especially when confronted with a handwritten Japanese menu. But truly, the food and drink are the main attraction—the reason these spots have thrived for generations. Familiarity with a few key items will not only simplify ordering but also enhance your entire experience. Consider this your cheat sheet to mastering yokocho cuisine.

Grill Game Strong: Yakitori and Motsuyaki

The unquestioned star of yokocho food is anything skewered and grilled over charcoal. The smoke filling the alley? That’s its source—it’s the heart and soul of the yokocho.

Yakitori (grilled chicken skewers) is the universal favorite. But this isn’t just plain chicken breast. Yokocho chefs embrace nose-to-tail eating. You’ll find momo (thigh), juicy and flavorful; negima (thigh and leek), a timeless combo; tsukune (chicken meatballs), often paired with a raw egg yolk for dipping; kawa (skin), grilled to crispy golden perfection; hatsu (hearts), chewy and satisfying; and nankotsu (cartilage), delivering a crunchy twist. Skewers typically come seasoned with either shio (salt) or tare (a sweet-savory soy glaze). Pro tip: trust the chef’s recommendation on the best seasoning for each cut.

Motsuyaki is the more daring cousin of yakitori, meaning grilled offal, usually pork. This is authentic salaryman soul food. Don’t hesitate! Items like kashira (pork cheek), shiro (intestines), and tan (tongue) are packed with flavor when grilled over charcoal and form a cornerstone of yokocho fare. They pair perfectly with a strong drink.

Soul in a Bowl: Nikomi and Motsuni

Almost every yokocho features a large pot simmering on the counter, filled with a fragrant, hearty stew. This is likely nikomi or motsuni, the ultimate comfort food. Nikomi refers to a long-simmered stew, often made with beef sinew (gyu-suji), tofu, and daikon radish in a miso or soy-based broth. It’s rich, savory, and melts in your mouth. Motsuni is a similar dish made with pork or beef offal, slow-cooked until tender. It’s robust, deeply flavorful, and warms you from within. Ordering a bowl signals you know what’s what. It’s an ideal dish for chilly nights and pairs wonderfully with sake or shochu.

Liquid Courage: The Definitive Drink Guide

First things first: you must order a drink. It’s an unspoken rule. Food comes after. The drink menu is usually straightforward but hits all the essentials.

Toriaezu Biru: Meaning “a beer for now,” this phrase kicks off most evenings. You’ll almost always get a crisp, cold Japanese lager like Asahi, Kirin, or Sapporo. It’s a perfect palate cleanser.

Nihonshu (Sake): The classic choice. Don’t get overwhelmed by brands unless you’re a connoisseur. Simply order it atsukan (hot) or hiya (chilled/room temperature). Hot sake, served in a small ceramic tokkuri flask and sipped from tiny ochoko cups, offers the quintessential yokocho experience, especially in winter.

Shochu Highball (Hai-boru): The salaryman’s fuel. A simple, refreshing mix of Japanese whisky (or shochu) and super-carbonated soda water, served tall with ice. It’s clean, crisp, and dangerously easy to drink. Highballs are a staple and an excellent choice if you plan on having more than one.

Shochu: A distilled spirit made from sweet potatoes, barley, rice, or buckwheat. It’s more rustic and often has a higher ABV than sake. You can enjoy it on the rocks, mixed with cold water (mizuwari), or hot water (oyuwari), which brings out its aroma.

Chuhai: A shochu highball with fruit-flavored syrup or juice. Lemon, grapefruit, and oolong tea are classic options. These are sweet, fizzy, and immensely popular.

Yokocho Etiquette 101: How to Navigate Like a Local

Alright, so you’ve found your alley and know what to order, but how should you behave? Yokocho have their own unspoken rules and social customs. Following them not only shows respect but also makes your experience smoother and more enjoyable. It’s all about honoring the space and the people within it.

The Unwritten Rules of the Alley

First, the otoushi. When you sit down, you’ll often be served a small appetizer you didn’t order. This is the otoushi, functioning as a table charge. Don’t send it back; it’s part of the deal. Think of it as your ticket to the seat. It’s usually something simple like edamame, pickled vegetables, or potato salad.

As mentioned, always order a drink first. It’s the first thing the master will ask for. Food orders come second. It’s just how the rhythm of the place flows.

These spots are tiny. Don’t take up more space than necessary. Keep your bags tucked under your stool or in a designated area. Be mindful of your elbows—you’ll be sitting very close to your neighbors, which is part of the charm. This closeness invites conversation, so if a local strikes up a chat, go with it! But also read the room; if others are having a private conversation, give them their space.

Cash is King, Space is Queen

This is important. Many, if not most, traditional yokocho are cash-only. Don’t show up expecting to pay by card. Bring enough yen to cover your bill. It keeps things simple and quick, which is the yokocho way. When it’s time to pay, you’ll often just say “Okaikei onegaishimasu” (Check, please), and the master will tally it up, sometimes using an old-fashioned abacus.

Respecting the space also means not overstaying your welcome, especially when it’s busy and people are waiting. The general idea of a yokocho is to have a few drinks and a couple of dishes, then move on. Lingering for hours over a single drink is considered bad manners when there’s a line outside. The goal is to enjoy the vibe, then graciously make room for the next guest.

Mastering the Art of “Hashigo-zake” (Bar Hopping)

This brings us to one of the most cherished yokocho traditions: hashigo-zake, or ladder drinking. It’s the Japanese art of bar hopping. Instead of staying in one spot all night, the true yokocho experience involves visiting several venues. You might enjoy yakitori and beer at the first place, some nikomi and hot sake at the second, and a final highball at a third. Each stop offers a new atmosphere, new food, and new people. This is the best way to truly savor the diversity of a yokocho alley. It keeps the energy lively and lets you sample a wide range of what the area has to offer. So embrace the transient spirit of the yokocho. Have a quick round, pay your bill, thank the master (“Gochisousama deshita!”), and step back into the lantern-lit alley in search of your next adventure.

The Last Call: Why Yokocho is the Soul of Japan You’ve Been Searching For

In a country that often seems to be hurtling toward the future, the yokocho stands as a defiant, beautiful link to the past. It’s a living museum where you can touch the exhibits, taste the history, and become part of the story. Stepping into one of these alleys is more than just a night out; it’s a lesson in Japanese history, sociology, and the enduring strength of community. It reminds us that beneath the polish of modern Japan lies a deep appreciation for simple, unpretentious moments of connection—sharing a laugh with a stranger, watching a master at work, and savoring food made the same way for generations. It’s an experience that’s messy, human, and utterly genuine. So, on your next trip to Japan, I challenge you to stray from the main road. Look for the glowing red lantern, take a deep breath of smoky, savory air, and slide onto that tiny wooden stool. You’ll likely find that the best souvenirs aren’t things you can buy, but the hazy, warm memories made in a small bar tucked away in a forgotten alley. It’s the real Japan, and it’s waiting for you.