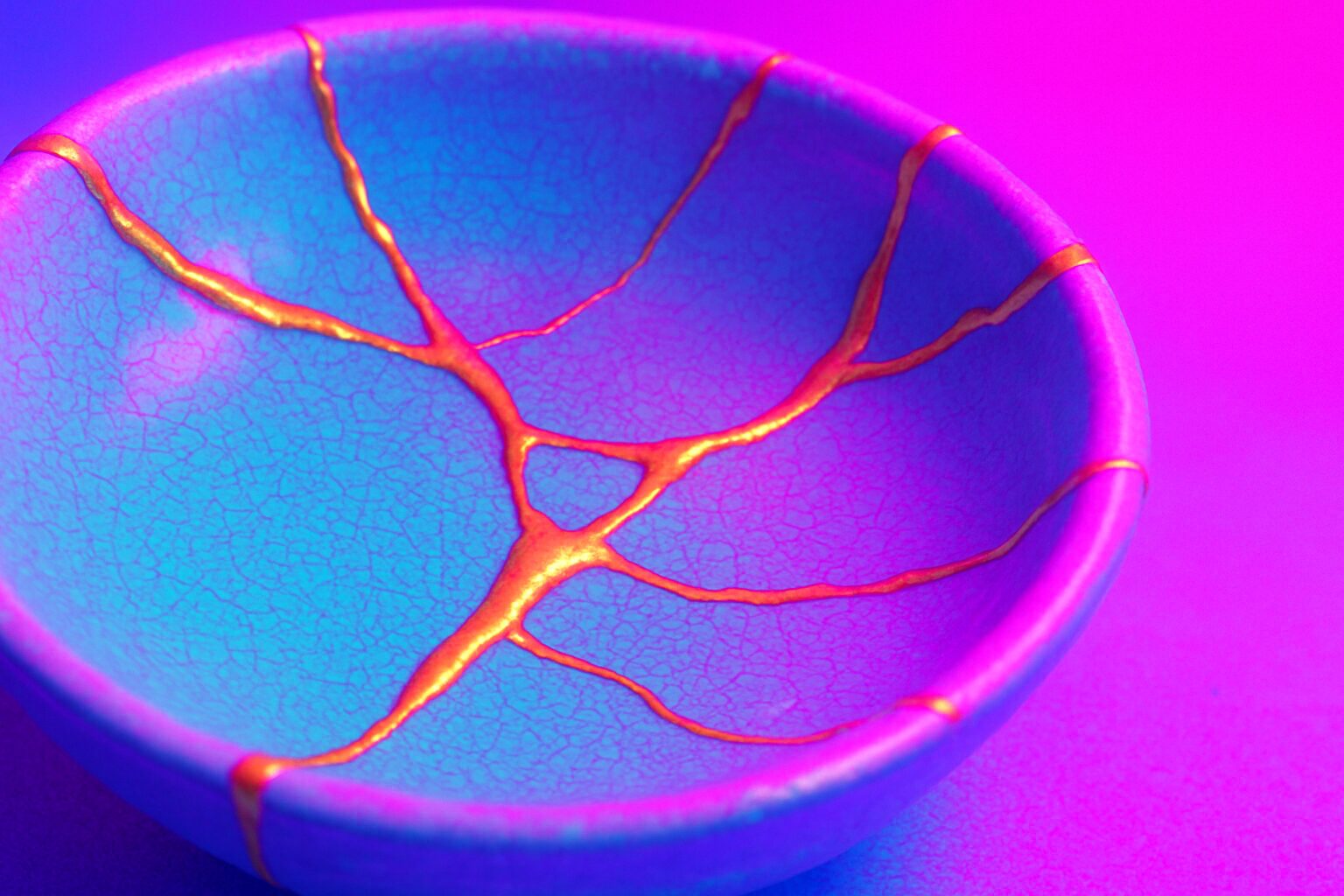

Alright, so you’ve done the Japan thing. You’ve scrambled across Shibuya Crossing, snapped a selfie with the deer in Nara, and maybe even slurped down some life-changing ramen in a Fukuoka yatai. You’re officially a repeat visitor, part of the inner circle. The neon glow of Tokyo and the serene temples of Kyoto feel familiar, like a favorite song. But now you’re craving something deeper, a layer of Japan that doesn’t always make it onto the glossy travel brochures. You’re ready to get past the surface and vibe with the country’s actual soul. If that’s you, then let’s talk about Kintsugi. It’s not a place, but a philosophy you can hold in your hands. It’s the art of repairing broken pottery not by hiding the cracks, but by highlighting them with gold. It’s a total glow-up for broken things, transforming them into something more beautiful and valuable than they were before. This isn’t just about DIY crafts; it’s a deep dive into the heart of Japanese aesthetics, a concept called wabi-sabi that finds epic beauty in imperfection. Forget chasing flawlessness; Kintsugi is about celebrating the scars, the history, and the journey. It’s the ultimate upcycled art, a quiet rebellion against our throwaway culture, and honestly, it’s one of the most authentically cool things you can explore on your next trip. It’s a slow, mindful experience that connects you to centuries of Japanese craftsmanship and a way of seeing the world that might just change how you see your own beautiful breaks and imperfections. Let’s get into it.

The Lowdown on Kintsugi: It’s More Than Just Glue and Gold

Before you go hunting for these golden-seamed treasures or sign up for a workshop, it’s worth getting the full story. Kintsugi, or “golden joinery,” is far more than just a simple repair technique. It’s a practice deeply rooted in history, philosophy, and a profound appreciation for the life of an object. It’s the kind of story that transforms the way you see a simple ceramic bowl, revealing a universe of meaning. In our era of fast fashion and disposable goods, spending weeks or even months lovingly restoring a single broken cup feels revolutionary. It’s a quiet act of defiance affirming that this object holds value, its history matters, and its scars are not a mark of shame but a symbol of resilience. It challenges conventional ideas of beauty, inviting us to find charm not in perfect flawlessness, but in the unique, unrepeatable story of damage and restoration. This is the essence of Kintsugi, and understanding it is essential to truly appreciating the art form.

A History That’s Truly Engaging

Like all great things, Kintsugi has an incredible origin story. We must rewind to the 15th century, during Japan’s Muromachi period. The central figure is Ashikaga Yoshimasa, the eighth shogun of the Ashikaga shogunate. He was a major patron of the arts, though perhaps not the best political leader. While political turmoil unfolded, Yoshimasa focused on cultivating what became the Higashiyama culture, a movement celebrating arts such as the tea ceremony (chanoyu), ikebana (flower arranging), and Noh drama. He fully embraced that refined aesthetic life. The legend goes that the shogun accidentally broke his favorite celadon tea bowl, a precious piece imported from China. Distraught, he sent it back to China for repairs. Months later, it returned—repaired, but disfigured with crude metal staples. It worked, of course, but was a total eyesore, having lost all its elegance. Imagine the disappointment—his prized bowl, a centerpiece of his beloved tea ceremonies, now looking like it had been through medieval surgery.

Yoshimasa, a man of refined taste, was not satisfied. He tasked Japanese artisans with finding a more beautiful way to repair it. This challenge sparked a repair revolution. Rather than hiding the cracks, these craftsmen had a breakthrough idea: what if the damage was celebrated? What if the repair itself became the object’s most beautiful feature? Using their expertise with urushi lacquer—a durable natural sap used in everything from furniture to armor—they began piecing the bowl back together. But they didn’t stop there. They dusted powdered gold over the still-tacky lacquer seams. The result was stunning. The break was not concealed; it was highlighted, transformed into shimmering golden rivers that endowed the bowl with a new, unique, and arguably deeper beauty. This was more than repair; it was rebirth. The bowl became not just a perfect celadon piece from China but a one-of-a-kind object infused with a Japanese soul, bearing the golden scars of its distinctive history. And just like that, Kintsugi was born. It quickly became deeply connected with the tea ceremony, where utensils showing age and character were prized over new, mass-produced perfection.

The Philosophical Foundation: Wabi-Sabi and Mottainai

To truly grasp Kintsugi, you need to understand the philosophical foundation it rests upon. Two central concepts shape it: wabi-sabi and mottainai. These are not just fancy Japanese words; they represent deeply ingrained cultural mindsets influencing everything from art to everyday life, offering a unique perspective that finds peace and beauty in places often overlooked.

Embracing the Wabi-Sabi Spirit

Wabi-sabi is notoriously difficult to translate directly into English because it’s more of an emotional atmosphere than a strict definition. It embodies the quintessential Japanese aesthetic of finding beauty in imperfection, impermanence, and incompleteness. It’s a mood. Let’s explore it further.

‘Wabi’ originally described the loneliness of living isolated in nature, far from society. Over time, it came to mean rustic simplicity, quietness, and understated elegance found in natural materials and processes. Picture the beauty of a rough, handmade ceramic cup, slightly uneven in shape, its glaze irregular. It’s the sensation of a quiet, misty morning, the scent of damp earth, the subtle texture of unbleached linen. Wabi is about appreciating humility, stripping away the unnecessary to discover pure, tranquil beauty. It stands in opposition to flashy, ostentatious displays of wealth. It’s calm, centered, and authentic.

‘Sabi’ refers to the beauty or serenity that emerges with age, when an object’s life and impermanence become visible in its patina, wear, or repairs. It’s the elegant decay and the evidence of time passing. Imagine the deep, dark sheen on a wooden temple floor worn smooth by centuries of pilgrims. Or the faded colors of an old kimono, the rust on an iron gate, or moss on a stone lantern in a serene garden. Sabi is the narrative an object tells through its aging. It reminds us that everything is transient, and there is profound, melancholic beauty in that impermanence.

Kintsugi beautifully blends these two ideas. The broken bowl exemplifies wabi-sabi. The break brings imperfection and chance. The gold mending doesn’t seek to restore flawless newness but embraces imperfection and elevates it. The golden seams represent the ‘sabi’—the visible history, the story of the object’s life, trauma, and healing. The finished piece embodies more wabi-sabi than the original, now carrying a richer story of impermanence and resilience. It is a physical poem celebrating the journey, flaws included.

The ‘Mottainai’ Moment: Cherishing and Respecting

Another vital concept embedded in Kintsugi is ‘mottainai.’ This Japanese word roughly conveys a sense of regret over waste, but it goes beyond the idea of “waste not, want not.” Mottainai reflects a deep cultural belief that everything possesses a soul or essence and that wasting something is to disrespect that essence. It applies from not leaving a single grain of rice in your bowl to repairing objects rather than discarding them. It’s a philosophy rooted in gratitude and respect for resources, objects, and even time. In today’s environmental crisis, this ancient concept feels especially relevant.

Kintsugi is the ultimate expression of mottainai. When a cherished tea bowl breaks, the mottainai spirit insists it would be a tragedy to simply throw it away. The bowl carries history, having served meaningful human moments. Discarding it wastes not only material but also its story. Kintsugi honors the object by granting it a second life. But it does more than rescue it from the landfill; it elevates it. The repair adds new value—both monetary and philosophical. The object becomes a testament to mottainai principles, a beautiful, functional reminder to cherish what we have, recognize potential in broken things, and treat the world around us with care and respect. It is the original form of upcycling, long before the term became popular.

The Kintsugi Glow-Up: Peeping the Process

Grasping the philosophy is one thing, but witnessing the meticulous, patient process of Kintsugi is what truly astonishes you. This isn’t a quick repair with superglue. Traditional Kintsugi is a painstaking art that can take months, requiring immense skill, patience, and a deep knowledge of natural materials. It’s a slow, meditative interaction between artisan and object, a process as beautiful as the final piece.

It’s a Whole Mood: The Artisan’s Workspace

Picture stepping into a Kintsugi master’s studio. The atmosphere is immediately calming. It’s not a sleek, modern workshop but more likely a small, quiet room, perhaps overlooking a tiny garden. The air is still, faintly scented with earthy lacquer and wood. Light filters through a paper shoji screen, illuminating dust particles dancing in the air. The space is filled with an organized clutter of tools that seem passed down through generations. Shelves hold broken ceramics, each patiently awaiting transformation. Rows of small porcelain dishes contain vibrant pigments and metallic powders—gold, silver, brass, copper. Brushes of all sizes, some incredibly fine and made from soft cat or mouse hair, each serve a specific purpose. Bamboo spatulas (heras) are used for mixing and applying lacquer, alongside sharpening stones for tools and soft silks for polishing.

At the center stands the artisan, working with quiet, intense focus. Each movement is deliberate and calm. There’s no loud machinery—only the soft sound of a brush on ceramic, the gentle scraping of a spatula. The mood is reverent, deeply concentrated. It feels less like a repair shop and more like a sanctuary, a place where broken things are healed and reborn. It’s a powerful tribute to slow craftsmanship in a world obsessed with speed and instant gratification.

Step-by-Step, but Make It Art

The process is a lesson in patience. Each step must be perfectly finished before moving on, and the drying and curing times for urushi lacquer cannot be rushed. It’s a journey of many small, precise actions leading to a stunning transformation.

The Breakup (and Makeup)

It all starts with the break. Sometimes it’s a tragic accident—a cherished heirloom slipping from one’s hands. For students, a piece may be intentionally broken to practice repairing. The first crucial step is to gather every shard, no matter how small. Like a detective at a crime scene, the artisan carefully collects all fragments and lays them out. Next comes the meticulous cleaning of each piece’s edges to ensure a perfect fit and strong bond. Any dirt or grease could weaken the repair. The artisan then dry-fits the pieces together like a complex puzzle, visualizing the break lines—the ‘keshiki’ or ‘scenery’ of the cracks that will become the artwork’s highlight.

The Secret Sauce: Urushi Lacquer

The heart of Kintsugi is urushi, the sap of the Rhus verniciflua tree native to East Asia. This natural, food-safe adhesive and coating is incredibly strong and resistant to water, heat, and acid, used in Japan for over 9,000 years. However, raw urushi contains a compound that can cause a severe skin reaction, akin to poison ivy. Artisans build immunity over years, handling it with great respect and care.

For bonding, the artisan makes a paste called ‘mugi-urushi’ by mixing raw urushi with water and rice or wheat flour. This creates a strong yet slightly flexible natural glue. Using a fine spatula, the paste is carefully applied to one broken edge. The fragments are pressed together firmly and held with tape or clamps. The real magic begins as the piece is left to cure.

The Long Wait: Patience is a Vibe

Here, modern impatience is truly challenged. Urushi doesn’t dry by evaporation but cures through polymerization, needing humidity (70-85%) and a stable temperature (20-25°C). The repaired object is placed in a special wooden cabinet called a ‘muro’. Then, you wait. Depending on lacquer thickness and conditions, curing takes one to two weeks. Missing chips are filled layer by layer with a mix of urushi, sawdust, and clay powder called ‘sabi-urushi’. Each layer must cure in the muro for days, then be carefully sanded before the next is applied. Filling a single small chip can take weeks. This slow, intentional waiting teaches respect for natural processes and forces the artisan to slow down and stay present—a profound antidote to our desire for instant results.

The Golden Hour

Once all structural repairs are done, cracks are filled and sanded perfectly smooth, and the piece is whole again, it’s time for the final, iconic stage: the glow-up. The artisan first paints a fine, precise line of high-quality pure urushi lacquer (often red or black, providing a rich background for gold) over the seams. Timing is crucial—the lacquer must be tacky, not wet. Then, using a delicate brush called a ‘kebo’ or a soft bamboo tube called a ‘makizutsu,’ the artisan gently sprinkles finely powdered gold (kinpun) onto the lacquered lines. The gold adheres to the tacky urushi, forming the brilliant, signature seam. Excess powder is carefully brushed away.

After another curing period in the muro, the golden lines are gently polished, usually with silk or a special agate stone, to reveal their warm, lustrous shine. The transformation is complete. The object is not merely repaired; it is reborn. Its scars have become its most stunning feature—a shimmering testament to its journey. The piece is whole, beautiful, and stronger than ever before.

Your Kintsugi Quest: Where to Vibe with Golden Scars

Alright, so you’re captivated by the Kintsugi aesthetic. You want to see these exquisite pieces up close, maybe even try your hand at the craft. As a returning visitor, you have the advantage of exploring beyond the main attractions to discover these more subtle, artistic experiences. Japan is a treasure trove for craft enthusiasts, and hunting for Kintsugi can be a rewarding journey itself, leading you down quiet backstreets and into charming little shops you might otherwise overlook.

Hunting for Treasure: Galleries and Antique Shops

The best way to find authentic, high-quality Kintsugi is to visit antique shops, craft galleries, and specialty tableware stores. Here, you’ll encounter pieces with rich histories, repaired using traditional, time-intensive methods. Searching for them is a dive into the heart of Japan’s aesthetic culture.

In Kyoto, the ancient imperial capital, you’re spoiled with options. Head to the Higashiyama district, with its sloping streets leading up to Kiyomizu-dera Temple. This area is filled with ‘yakimono’ (pottery) shops. While many sell new items, some dedicate corners to antiques or works by local artists, where you can often find a stunning Kintsugi bowl or plate. The Gion district, famous for its geishas, also hosts several high-end antique stores tucked away on its historic streets. Walking through these neighborhoods feels like stepping back in time, and stepping into a quiet, incense-scented shop to admire a golden-seamed vessel is a truly magical experience. Don’t forget Teramachi Street, an arcade brimming with an eclectic mix of shops, including some excellent antique dealers where you might uncover a hidden gem.

Tokyo, despite its modernity, retains pockets of old-world charm ideal for Kintsugi hunting. Yanaka is a fantastic neighborhood to explore. Having escaped the bombings of World War II, it preserves a captivating, nostalgic ‘shitamachi’ (downtown) atmosphere. Stroll down Yanaka Ginza, a lively shopping street, and explore the side alleys to find small family-run shops. Kagurazaka, with its Parisian vibe and winding stone-paved alleys, is another excellent spot, home to sophisticated galleries and craft shops. For a more contemporary approach, the chic boutiques of Daikanyama sometimes feature modern artists incorporating Kintsugi techniques into their work.

For a truly immersive experience, consider a trip to Kanazawa. Often dubbed “Little Kyoto,” this city on the Sea of Japan coast is a powerhouse of Japanese craft, especially renowned for its gold leaf production (supplying 99% of Japan’s domestic gold leaf) and lacquerware. Here, you can not only see finished Kintsugi pieces but also visit workshops to witness the origins of the raw materials, adding a deeper appreciation for the art.

When shopping, remember that authentic Kintsugi is an investment. The price reflects the extensive time, skill, and costly materials (real urushi and pure gold powder) involved. You will encounter cheaper, modern versions made with epoxy resin and synthetic gold paint. These can be attractive but lack the depth, durability, and philosophical essence of genuine pieces. To tell the difference, look for the subtle warmth and gentle luster of real gold, and the organic, slightly raised texture of the urushi seam. If unsure, ask the shopkeeper; reputable stores will gladly explain the piece’s provenance.

Get Your Hands Dirty: The Workshop Experience

While admiring Kintsugi is delightful, trying it yourself is transformative. It’s the ultimate way to personally connect with the philosophy. Handling the materials, experiencing the concentration needed to fit the pieces together, and the satisfaction of applying the golden finish fosters deep respect for the artisans who master this craft. Many studios in major cities now offer workshops for foreigners, often with English-speaking instructors.

These workshops usually provide a simplified, condensed version of the traditional process. You won’t use traditional urushi, which takes weeks to cure and isn’t practical (or safe for beginners, due to its skin-irritant properties). Instead, you’ll likely work with modern, quick-curing lacquer or food-safe epoxy, paired with brass or other imitation gold powders. This permits finishing a piece within a single few-hour session. You might be given a pre-broken tile or a small dish to repair.

I remember my first workshop in a quiet corner of Kyoto. Our sensei was a gentle older woman who spoke with calming reverence about the process. She began by sharing the story of Yoshimasa and his tea bowl. Then she handed each of us a small shattered plate. At first, I felt anxious—how could I make this broken mess beautiful? But as she guided us step-by-step—carefully cleaning edges, mixing adhesive, painstakingly fitting the pieces—a deep focus took over. The rest of the world faded away. It was just me, the broken plate, and the quiet rhythm of the work. The most magical moment came at the end, dusting golden powder over the seams. As I brushed away the excess and saw the shimmering lines emerge, I felt genuine excitement. My broken plate had become something entirely new, something I had healed with my own hands. I left the studio not only with a unique keepsake but with a tangible connection to the wabi-sabi philosophy. It was a lesson in patience, acceptance, and the transformative power of care.

Booking these workshops is usually straightforward. You can find them on experience-booking platforms or by searching “Kintsugi workshop Tokyo/Kyoto” online. It’s wise to book ahead, especially during peak travel seasons. Don’t worry about being a creative genius; the instructors are there to support you, and the goal isn’t perfection but participating in a beautiful, mindful process.

Living the Kintsugi Life: It’s More Than Just Pottery

The beauty of discovering Kintsugi is that its impact continues long after you leave the gallery or workshop. It’s a concept that permeates your consciousness and transforms how you perceive the world. While it’s a practical art form, it also serves as a powerful metaphor for life, resilience, and the beauty found in a well-lived existence.

Bringing the Vibe Home

If you choose to bring a piece of Kintsugi into your home, it becomes more than just decoration—it serves as a daily reminder of the philosophy. A Kintsugi bowl isn’t meant to be hidden away in a cabinet. Traditional Kintsugi is food-safe and durable, so it can be used (with gentle care—hand wash only!). Imagine beginning your day with tea in a cup that has been broken and beautifully restored. It’s a quiet, mindful moment that anchors you in the values of acceptance and resilience. These pieces spark conversation, giving you the chance to share their story and philosophy with friends and family. A Kintsugi object in your home becomes a focal point for reflection, a tangible piece of wisdom that radiates calm, wabi-sabi energy throughout your space.

The Big Picture: Embracing Your Own Golden Scars

This is the core lesson. Beyond any souvenir, Kintsugi imparts a profound life insight. We live in a society that idolizes youth, perfection, and flawlessness. We’re taught to hide our weaknesses, conceal our scars, and appear as if we have it all together. We filter our photos, craft curated online personas, and often carry a deep shame about our mistakes and hardships. Kintsugi presents a radical, healing alternative. It shows us that our breaks, traumas, and struggles are not to be concealed. They are essential parts of our story. They shape us, deepen our character, and build our resilience. When we accept—and even honor—these aspects of ourselves, we become stronger, more compelling, and more beautiful than before.

Reflect on moments in your life when you were “broken”—a failed project, a lost job, a broken heart. The Kintsugi philosophy invites us to view these not as endings but as chances for golden repair. These painful experiences can create the most beautiful patterns in our lives, if we have the courage to mend ourselves with self-compassion and resilience. Our “scars” become proof that we have lived, loved, and overcome. They stand as a testament to our strength. Embracing this mindset is liberating. It frees us from the impossible quest for perfection, helping us find peace and beauty in our authentic, imperfect, wabi-sabi selves.

So, on your next trip to Japan, venture off the well-trodden path. Seek out the quiet beauty of a golden seam on a broken bowl. Spend an afternoon in a workshop, experiencing the mindful act of repairing something with care. It’s more than an art tour; it’s an invitation to explore a deeper aspect of Japanese culture and, in doing so, to discover a more compassionate and beautiful way of seeing the world—and yourself. Forget perfection. The true beauty, the real story, lies in the golden scars.