Alright, fam, let’s have a real talk. You’ve done Tokyo. You’ve seen the temples in Kyoto, maybe even hit up Osaka for that legendary street food scene. You’re not a newbie anymore; you’re on that next-level Japan journey. You’re searching for a vibe, a feeling, something that gets right to the heart of this place, especially when the winter air hits different. When the sun dips early and the city starts to sparkle with a frosty edge, there’s a specific kind of magic that comes alive in the quiet backstreets. It’s a warm, golden glow spilling from a tiny stall, a cloud of savory steam that promises comfort and connection. This, my friends, is the world of the oden yatai, and it’s about to become your new winter obsession. Forget the flashy restaurants for a night. We’re diving into something real, something that’s been warming the souls of locals for generations. An oden stall isn’t just a place to eat; it’s a temporary sanctuary from the cold, a communal hearth where strangers share a few moments of warmth over a simmering pot of pure deliciousness. It’s where the city’s pulse slows down to a gentle simmer, just like the dashi broth it’s built around. This is the Japan you’ve been looking for, the one that whispers stories in the steam. It’s the ultimate cozy, no cap. This is your portal to that experience, a guide to chasing the steam and finding your spot at the counter.

After warming up with oden, you might be looking for a place to stay, and for a truly luxurious experience, consider the latest strategic alliances between global luxury hotels and Japanese OTAs.

The Vibe Check: Decoding the Oden Yatai Atmosphere

Before we even discuss the food, you need to grasp the entire atmosphere. The oden yatai experience is a complete sensory immersion. It’s less a restaurant and more a fleeting micro-community gathered around a bubbling pot. Imagine this: you’re strolling down a lane in a neighborhood like Shinjuku or Ebisu, the neon lights of the main street fading in the distance. The air is crisp, your breath visible, and then you spot it—a single red lantern, the akachochin, gently swaying. It’s an iconic beacon, a warm, inviting signal in the cool, dark blue night. It promises heat, flavor, and maybe a touch of magic. As you approach, the first thing that strikes you is the steam. It billows into the night air, carrying an incredible aroma—a savory, slightly sweet, deeply comforting scent of dashi broth simmered for hours. It’s a smell that feels like a hug. You pull back the canvas flaps, the noren, and step into another world. The space is tiny, almost impossibly so. Maybe eight to ten seats packed around a wooden counter worn smooth by decades of use, marked by countless elbows and bowls. The light is dim and golden, cast by that single lantern and perhaps a bare bulb, creating an intimate, almost theatrical ambiance. The star of the scene, the oden pot, takes center stage. It’s a large, square, partitioned vessel—a hot tub of simmering goodness where various ingredients gently bob in the amber broth. Steam rises continuously, catching the light and softening the faces of fellow patrons. This steam creates the yatai’s unique sense of privacy and closeness; you’re close enough to brush elbows with the person beside you, yet it feels like your own little world. The sounds are just as crucial as the sights and smells. There’s the soft, constant goto-goto of simmering broth, a sound as comforting as a crackling fire. You’ll hear a low murmur of conversation, never loud—just quiet chatter of salarymen unwinding after a long day, a couple on a date, or an old-timer chatting with the stall master. There’s the clink of ceramic sake cups, the scrape of chopsticks against a bowl, and the calm voice of the master—or taisho—taking an order. It’s a subtle symphony. This isn’t a place for loud talk or phone calls. It’s a place to be present, to listen, to observe. The feeling is one of shared refuge. Everyone here searches for the same thing: warmth, comfort, and a moment of peace. You’re all equals at the oden counter. It doesn’t matter what you do for a living or where you come from. For the time you’re there, you’re simply part of this small, temporary family, united by the cold outside and the warmth radiating from the pot.

More Than Just Broth: Getting Intimate with the Oden Lineup

Alright, let’s dive in. The main attraction—the simmering pot—is a universe of flavor and texture, and mastering it is essential. Don’t be overwhelmed by its vast variety. Think of it as a treasure hunt where every pick is a winner. At the heart of it all is the dashi, the broth. This isn’t just salty water; it’s the soul of oden. Carefully crafted, it’s usually made from kombu (kelp) and katsuobushi (dried, smoked bonito flakes), seasoned with soy sauce, mirin, and sake. Every stall owner guards their own secret dashi recipe, perfected over years. Throughout the evening, the broth improves as all the ingredients simmer together, lending unique flavors that create a complex, evolving taste impossible to replicate. Now, let’s talk about the players. First up are the absolute classics—the ride-or-dies of the oden world. Daikon radish is, without question, the true MVP. It enters the pot as a firm, stark white disc and emerges hours later as a translucent, amber gem. It fully absorbs the dashi, and biting into it bursts with savory, soupy goodness that practically melts in your mouth. A perfectly cooked oden daikon is truly a work of art—no exaggeration. Next is the humble boiled egg, Tamago. Simmered for hours, the egg white firms up, infused with broth flavor, while the yolk becomes a jammy, creamy center of pure delight. Simple, yet essential. Then we have the tofu family. Atsuage is a block of deep-fried tofu—the crisp outer skin softens in the broth, acting like a sponge that soaks up all that dashi goodness, while the inside remains creamy. Ganmodoki is a tofu fritter mixed with finely chopped vegetables like carrots, gobo (burdock root), and black sesame seeds, lending it a more complex texture and flavor. It’s an absolute must-try. Moving on to intriguing textures: Konnyaku and Shirataki. Both come from konjac yam, giving them a firm, gelatinous, almost bouncy feel. Konnyaku usually appears as a grey, speckled triangle or block, while Shirataki are thin, translucent noodles often tied into neat bundles. They lack strong flavor on their own but serve as excellent carriers for dashi, offering a satisfying textural contrast to the softer items. Now to the fishcake squad, the nerimono. This broad category is where things get really exciting. Hanpen is a favorite—white, square, incredibly light and fluffy, with a texture almost like marshmallow. It floats atop the broth and soaks in the flavors beautifully. Chikuwa is a tube-shaped, slightly chewy fishcake that’s grilled, giving it a faint smoky taste. Satsuma-age is a fried fishcake, often with vegetables mixed in, denser and sweeter in flavor. Each offers a completely different experience. For those feeling adventurous eager to level up, try Mochi Kinchaku—a pouch of fried tofu (aburaage) hiding a surprise inside: a soft, gooey rice cake (mochi). When you bite into it, the savory, dashi-soaked tofu yields to this stretchy, chewy, slightly sweet mochi. It’s a total game-changer. Another top-tier option is Gyusuji, or beef tendon. Simmered for hours until meltingly tender and gelatinous, it falls apart at the slightest touch of chopsticks. It adds a rich, meaty depth to both your bowl and the broth—pure, unadulterated comfort. For those seeking the real deep cuts, proving their oden expertise, there’s Chikuwabu. This Tokyo specialty is often mistaken for fishcake but is actually made from wheat flour. It’s dense, chewy, and divisive—people either love it or hate it. You have to try it to find out which side you’re on. It’s an excellent broth soaker, but its texture is what truly defines it. The list goes on—sausages, cabbage rolls (roru kyabetsu), potatoes, gobo-maki (burdock root wrapped in fish paste), and much more. The magic lies in the combination. A perfect oden bowl brings together a variety of flavors, textures, and shapes. It’s a carefully curated collection of comfort.

Yatai Etiquette & How to Order Like a Pro

Navigating an oden yatai for the first time may feel a bit intimidating, but the rules are straightforward and the atmosphere is very relaxed. It’s all about respect—for the space, the master, and your fellow diners. First things first: finding a seat. Yatai are small, so personal space is a rarity. If you spot an open seat, don’t hesitate. A simple nod to the person beside you and a quiet “sumimasen” (excuse me) as you squeeze in is all that’s needed. It’s part of the charm. Everyone gets it. Once you’re settled, take a moment to take it all in. The taisho will likely greet you with a soft “irasshai” (welcome). Now it’s time to order. Sometimes there’s a menu, but often there isn’t one, or it’s just a few handwritten items on the wall. The real menu is the simmering pot before you. Ordering is usually as easy as pointing. A polite “kore o kudasai” (this one, please) while gesturing at the daikon or tamago you want works perfectly. Don’t feel pressured to order everything at once. Oden is meant to be savored slowly. Start with two or three items, then order more as you go. This is a marathon, not a sprint. If you’re feeling completely lost, the magic phrase is “osusume wa nan desu ka?” (what do you recommend?). The taisho will gladly guide you. They may ask your preferences and then suggest a few choice items to begin with. This is the best way to discover new favorites and show trust in their expertise. They know what’s been simmering the longest and is at peak flavor. Your chosen items will be taken from the pot and served in a small bowl with a ladle of that glorious dashi. You’ll be handed the bowl and a pair of chopsticks. Now for the most important condiment: karashi. This sharp, potent Japanese mustard will be in a small pot on the counter. Use your chopsticks to take a tiny dab—and I mean tiny—and place it on the rim of your bowl or directly on an oden item. A little goes a long way and provides the perfect spicy kick to cut through the rich, savory broth. Don’t just stir it into the soup! That’s a rookie mistake. The dashi is sacred, and you want to enjoy its pure flavor. The karashi is meant to accent, not overpower. When it comes to fellow diners, the unspoken rule is to be considerate. Keep your voice low, don’t take up more space than necessary, and just be cool. While it’s a communal space, people often come to relax quietly. However, don’t be surprised if a conversation starts. A shared compliment to the taisho about the daikon or a question about what someone else is eating can easily lead to a friendly exchange. That’s where the magic happens—real, authentic interaction. When you’re ready to leave, settling the bill is simple. Just catch the taisho’s eye and say “o-kaikei onegaishimasu” (the bill, please). They might count your skewers and bowls, or simply have a legendary memory of your order. Yatai are almost always cash-only, so be sure to have some yen with you. A heartfelt “gochisosama deshita” (thank you for the meal) as you leave is the perfect way to end the experience. It’s a sign of respect and appreciation for the food and hospitality, and it’s sure to earn you a warm smile from the master.

The Perfect Pairing: What to Sip with Your Simmered Goodness

What you drink with your oden is just as important as what you eat. The right beverage not only quenches your thirst but also complements the flavors of the dashi, enhancing the whole cozy experience. This is your opportunity to explore some classic Japanese drinks perfectly suited for a cold winter night. The undisputed champion of oden pairings is, naturally, nihonshu, or sake. Specifically, on a chilly evening, you’ll want to choose atsukan—hot sake. Nothing warms you from the inside out quite like a small cup of heated sake. It’s served in a ceramic flask called a tokkuri, and poured into a tiny cup known as an ochoko. The warmth of the cup in your hands and the gentle aroma of the heated rice wine are all part of the ritual. The dry, savory notes of a quality junmai or honjozo sake beautifully cut through the richness of the oden, cleansing your palate between bites of different ingredients. Sipping hot sake while a cold wind blows outside the noren flaps is one of winter’s greatest pleasures—a vibe that’s simply immaculate. Another excellent choice, especially if you want something stronger, is shochu. This distilled spirit can be made from various ingredients such as barley (mugi), sweet potatoes (imo), or rice (kome). In winter, the preferred way to enjoy it is oyuwari, shochu mixed with hot water. This method releases the spirit’s aroma and makes it incredibly smooth and easy to drink. Imo-jochu, with its distinctive earthy and sometimes sweet notes, pairs particularly well with the deep flavors of oden. The taisho will prepare it for you, carefully balancing the ratio of shochu to hot water. It’s a drink that feels both rustic and refined, a favorite among yatai regulars. Of course, a classic Japanese beer is always a solid choice. A crisp, cold lager like Asahi, Kirin, or Sapporo offers a refreshing contrast to the warm, savory oden. The carbonation acts as a great palate cleanser, and that first cold sip after a mouthful of hot, dashi-soaked daikon is a truly elite experience. It’s a straightforward, no-fuss pairing that consistently delivers. If you’re not drinking alcohol, don’t worry—you’re not missing out on the cozy factor. Ordering a hot oolong tea (uroncha) is an excellent choice. The slightly toasty, earthy flavor of the tea complements the savory dashi and provides the internal warmth you’re seeking. Hot barley tea (mugicha) is another wonderful caffeine-free option with a nutty, comforting flavor. The key is to have a warm cup in your hands, completing the circle of comfort that the oden yatai offers. The drink is the final piece of the puzzle, the element that ties the entire sensory experience together into a perfect, soul-warming package.

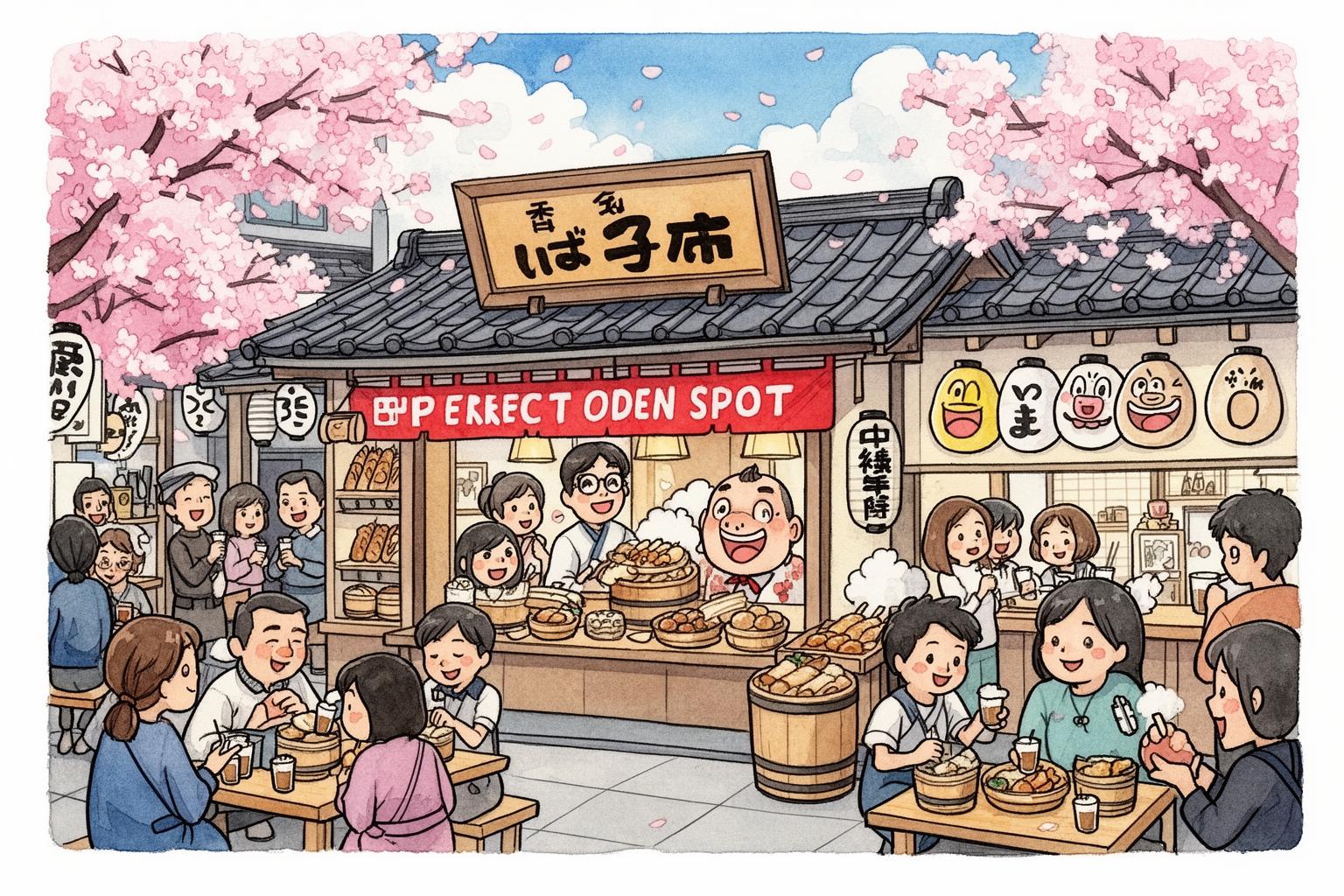

Beyond the Steam: Finding Your Perfect Oden Spot

So, you’re convinced by the idea, but where can you actually find these enchanting steam-filled havens? Part of the fun is the search—coming across a spot that just feels right. Yet, a little direction can help you know where to look. Your best bets are the famed yokocho, or alleyways, hidden within many of Japan’s major city districts. These narrow, lantern-lit paths are packed with tiny eateries and bars, offering a rich, atmospheric experience. Think of places like Omoide Yokocho in Shinjuku, also called “Piss Alley,” though it’s far more charming than the name implies. This maze of tiny lanes is constantly filled with smoke from yakitori grills and steam rising from oden pots, creating a sensory feast in the best way. Finding an oden stall here means you’ll be swept up in the vibrant, nostalgic energy of post-war Tokyo. Another treasure is Nonbei Yokocho, or “Drunkard’s Alley,” just steps from the Shibuya Scramble. This extremely narrow alley feels like a total throwback. The oden stalls here are tiny, often with only a few seats, offering an exceptionally intimate experience. Exploring these yokocho is an adventure in itself—it’s about following your senses. Chase the scent of dashi, spot the signature red lantern, and peek behind the noren curtains to see if the ambiance feels right. That said, some of the best discoveries are standalone stalls. These single yatai set up shop on quiet street corners, often near train stations in residential or business neighborhoods. Neighborhoods like Ebisu, Nakano, Ueno, or a bit further out like Kichijoji, are perfect places to wander and uncover these hidden gems. Finding one feels like being let in on a local secret. The crowd is mostly locals and regulars, and the atmosphere tends to be quieter and more personal. The taisho might have time to chat, offering a genuine slice-of-life glimpse of the city most tourists miss. Timing your search is also key. Oden yatai come alive at night. They usually open after sunset, around 6 or 7 PM, and often stay open late, serving a final warm meal to those catching the last train home. The ideal time is likely a weekday evening. On weekends, especially in popular yokocho, it can get quite crowded. A Tuesday or Wednesday night offers a more relaxed, local vibe and a better chance at scoring a coveted seat at the counter. Of course, oden is a seasonal treat. While some dedicated shops serve it year-round, the yatai culture truly flourishes in fall and winter. When temperatures drop, the number of stalls multiplies. A crisp, cold, clear night is the perfect backdrop for an oden outing. The contrast between chilly air and the warmth of the stall makes the experience all the more memorable and profound.

A Tale of Two Broths: Kanto vs. Kansai Oden

For those eager to dive deep into Japanese cuisine, it’s helpful to know that not all oden is the same. The broth—the heart of the dish—varies significantly by region. The two main styles you’ll encounter are Kanto-style from the Tokyo area and Kansai-style from the Osaka and Kyoto regions. Understanding these differences will seriously elevate your foodie knowledge and deepen your appreciation of the subtlety in Japanese flavors. Kanto-style oden, common in Tokyo, features a darker, more robust broth. The base remains kombu and katsuobushi, but a generous amount of dark soy sauce (koikuchi shoyu) gives the dashi a rich brown hue and a strong, savory, slightly sweet taste. It makes a bold statement. Ingredients simmered in this potent broth absorb its deep color and intense flavors. Kanto oden also includes some signature items you might not see elsewhere. Chikuwabu, a chewy wheat-flour cake mentioned earlier, is a quintessential Tokyo oden ingredient. Another is Suji, which in Tokyo refers to a type of white fishcake, often made from shark, ground into a paste and shaped. This differs from the gyusuji (beef tendon) popular nationwide. Overall, Kanto oden feels hearty, rustic, and deeply satisfying—ideal for a cold night in the city. Moving west to Kansai, the oden experience changes. Kansai-style oden emphasizes subtlety and refinement. The broth is a clear, golden liquid, achieved by using light soy sauce (usukuchi shoyu), which is actually saltier than dark soy but used sparingly to preserve the dashi’s delicate flavors. The focus lies on the pure taste of high-quality kombu, for which the region is renowned. The flavor is lighter, more elegant, letting the natural taste of each ingredient shine. The ingredients can vary as well. In Kansai, you’ll often find items like octopus (tako), and sometimes traditional but rarer ingredients such as Saezuri (whale tongue) and Koro (whale skin), reflecting the dish’s long history. Eating Kansai oden is a more delicate, nuanced experience—an exploration of umami artistry. While these two styles dominate, most oden stalls today have their own house-specialty broths that may fall somewhere between or feature unique twists. The taisho is an artist, and the dashi their masterpiece. But knowing the basic traits of Kanto and Kansai styles provides a useful framework. You’ll begin to notice the broth’s color, the distinct ingredients offered, and appreciate the regional heritage simmering in front of you, adding depth to an already rich culinary experience.

The Soul of the City: Oden and Japanese Culture

To truly appreciate oden, you need to recognize that it is far more than just a winter stew. It’s a cultural emblem, a dish deeply embedded in the heart of Japanese society. It stands for comfort, community, and a unique kind of beautiful, uncomplicated simplicity. Oden is the quintessential symbol of winter in Japan. Its appearance in convenience stores and the presence of yatai on street corners serve as seasonal markers, as unmistakable as the changing leaves. It sparks a collective, nationwide craving whenever the first real chill arrives. It’s the food people seek out for warmth and nostalgia, a flavor that recalls childhood winters and cozy family gatherings. Oden is comfort food in its purest and most basic form. Beyond personal solace, the oden stall functions as a vibrant social space. Its very design—a small group of people gathered around a central pot—encourages a unique kind of temporary community. In a society often seen as formal and reserved, the oden yatai is a space where barriers drop. The shared experience of braving the cold and savoring a simple hot meal creates an unspoken bond. It acts as a great equalizer. The salaryman in his costly suit and the construction worker in his gear are just two individuals enjoying a bowl of oden side by side. While not guaranteed, conversations with strangers come more naturally here than in nearly any other dining setting. It’s a microcosm of the city, a place where diverse lives briefly intersect in warmth. At the heart of this scene is the taisho, the master of the stall. This individual is more than a cook—they are the host, the mood curator, and often a quiet confidant to their regulars. The grace and efficiency with which a seasoned taisho manages their small domain is remarkable. They move with precision, selecting items from the pot, pouring drinks, and handling payments, all while maintaining a calm, watchful presence. They are the keepers of the flame—both literally and figuratively—tending the dashi and ensuring the sanctuary they’ve created remains welcoming to all who come. The whole experience also beautifully captures the Japanese aesthetic of wabi-sabi—an appreciation of beauty in imperfection and impermanence. The oden yatai isn’t polished or pristine. The counter is worn, the bowls may be chipped, and the seating is snug. Yet, there is profound beauty in this simplicity and authenticity. It’s a beauty born of use, history, and its role as a place of genuine human connection. The food itself is unpretentious and straightforward. There are no intricate techniques on display, just humble ingredients simmered carefully over time. This emphasis on the essential and the unadorned lies at the heart of oden’s allure and offers insight into a core aspect of Japanese culture.

So, the next time you’re in Japan and winter evening begins to fall, listen for that subtle call. Look for the warm glow of a red lantern down a dim alley. Don’t hesitate—lift the canvas flap and step inside. Let the steam warm your face and take a seat at the worn wooden counter. You’re not just having a meal; you’re taking part in a ritual. You’re finding a moment of connection in the vast city, a taste of a tradition that has warmed generations. It’s in these small, steamy corners you’ll discover the true soul of Japan’s streets, gently simmering in a pot of dashi, waiting for you to find it. Order something familiar, try something new, and savor the warmth. This is the experience that will stay with you long after you’ve gone, a memory as comforting and satisfying as the perfect bowl of oden itself. Go on—find your stall.