Yo, what’s the move? Megumi here, comin’ at you straight from Tokyo, but my heart? Right now, it’s living its best life down in Fukuoka, the undisputed capital of street food soul. If you’re scrolling for that next-level, authentic Japan experience, something that’s less tourist trap and more main character energy, then you gotta get with this. We’re talking about yatai, my friends. These aren’t just food stalls; they’re pop-up epicenters of pure vibes, sizzling eats, and straight-up human connection. Every single night, as the city lights of Fukuoka start to pop off, these magical little kitchens on wheels appear outta nowhere, lining the streets and waterfronts, calling out to anyone with an empty stomach and an open mind. This is Fukuoka’s pulse, its heartbeat, a tradition that’s no cap the realest deal. It’s where you’ll find the legendary Hakata ramen in its natural habitat, alongside a whole universe of grilled, stewed, and fried goodness. Forget your bougie, reservation-only spots for a night. This is where the city comes to life, one skewer and one bowl of noodles at a time. It’s gritty, it’s loud, it’s warm, and it’s about to be your new obsession. Bet.

To truly master the art of this iconic dish, you’ll want to level up your tonkotsu ramen knowledge.

The Vibe of Nakasu at Night: A Full-On Sensory Slay

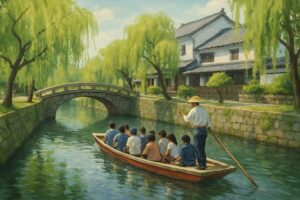

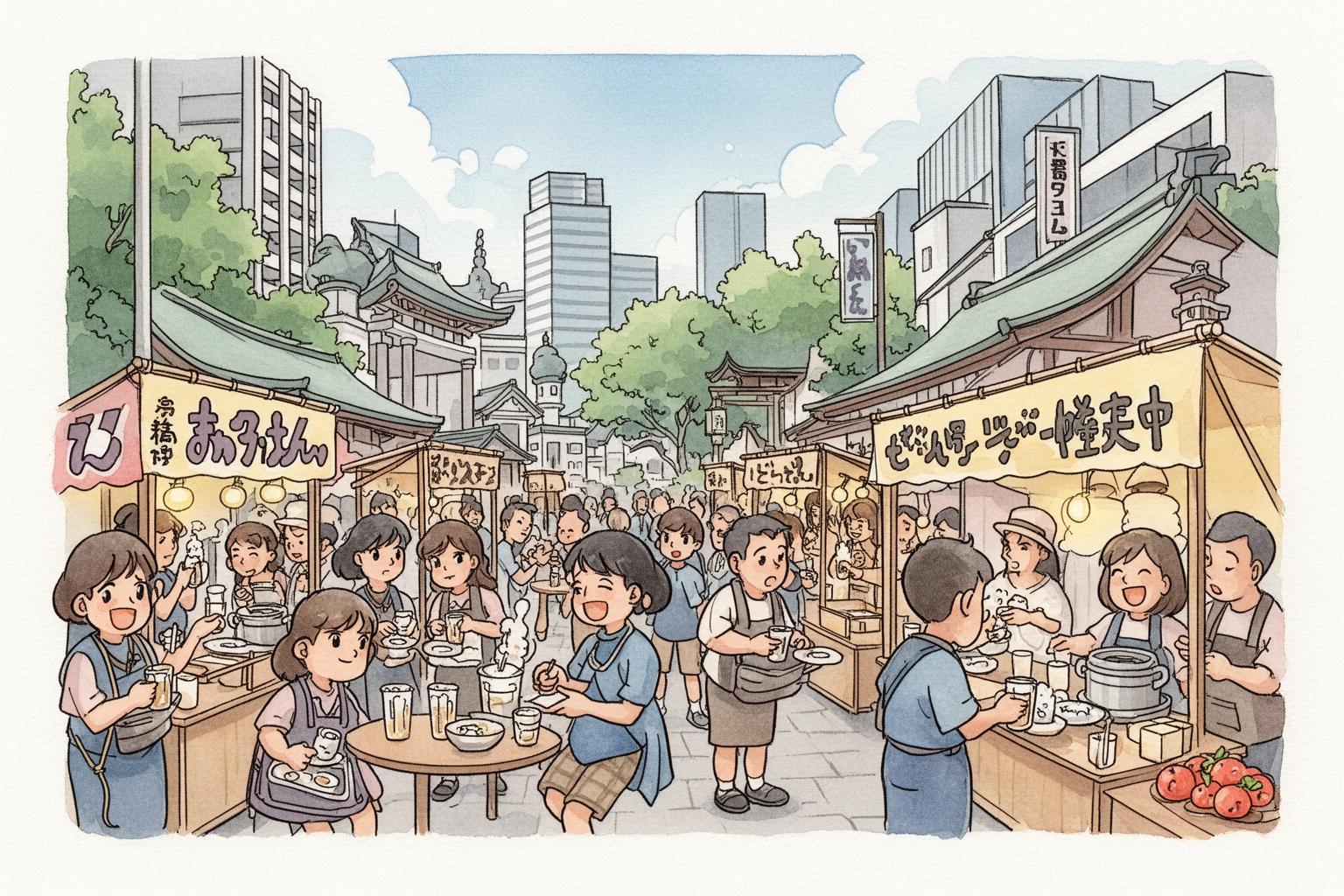

Imagine stepping out into the night in Fukuoka, where the very air holds an electric charge. You’re in Nakasu, an island nestled between two rivers, known as Fukuoka’s neon-lit entertainment hub. But as you stroll closer to the water, the atmosphere changes. The distant pulse of the city’s nightlife blends with something more intimate, more elemental. You catch the sizzle of food on a hot griddle, the cheerful clatter of chopsticks against ceramic bowls, and a swelling chorus of laughter and conversation mixing Japanese with languages from around the world. Then, you spot them—rows of yatai stalls, their warm golden glow spilling onto the pavement, creating cozy pockets of light against the dark, shimmering Naka River. Each stall is its own world, a tiny universe of culinary innovation. Steam rises from bubbling oden pots, carrying the savory, comforting aroma of dashi into the cool night. Smoke, rich with the scent of charcoal-grilled chicken and pork, curls skyward, signaling to passersby that something delicious is underway. It’s a full assault on the senses—in the most delightful way. The visual feast is just as captivating: vibrant noren curtains flutter at each stall’s entrance, handwritten menus display the day’s specials, and the taisho (stall owner) moves with focused, almost dance-like precision as they expertly flip skewers, pour drinks, and serve steaming bowls of ramen with practiced ease. The space is tight, indeed. You’ll find yourself sitting shoulder-to-shoulder with salarymen unwinding after work, young couples on dates, and fellow travelers wide-eyed with curiosity. This closeness isn’t a flaw; it’s a feature. It breaks down barriers. A simple smile to your neighbor can spark a conversation. A shared laugh over a spilled drink can lead to swapping travel stories. This is the heart of the yatai experience. It’s more than just eating; it’s about sharing a moment. The energy is kinetic, constantly evolving as people come and go, yet the underlying feeling is one of warmth and unpretentious joy. The reflection of the city’s skyscrapers and vibrant yatai lights on the river creates a scene straight out of a movie—the pure cinematic magic of Japan’s soul. Here, you can feel the city breathe and connect with its people on the most fundamental level: over good food and shared space. It’s a vibe unique to Fukuoka, and once experienced, you’ll carry that warmth with you long after the last bowl of ramen is gone.

More Than Just Ramen: The Yatai Foodie Bible

Alright, so everyone and their mother heads to Fukuoka for the ramen, and for good reason—it’s iconic. But thinking yatai are only about ramen is like thinking Tokyo is just about Shibuya Crossing. You’re missing the bigger, far more delicious picture. The yatai menu is a highlight reel of Japanese comfort food, each dish perfected for this unique, open-air experience. It’s a culinary adventure where every option is a winner.

Tonkotsu Ramen: The OG Fukuoka Showstopper

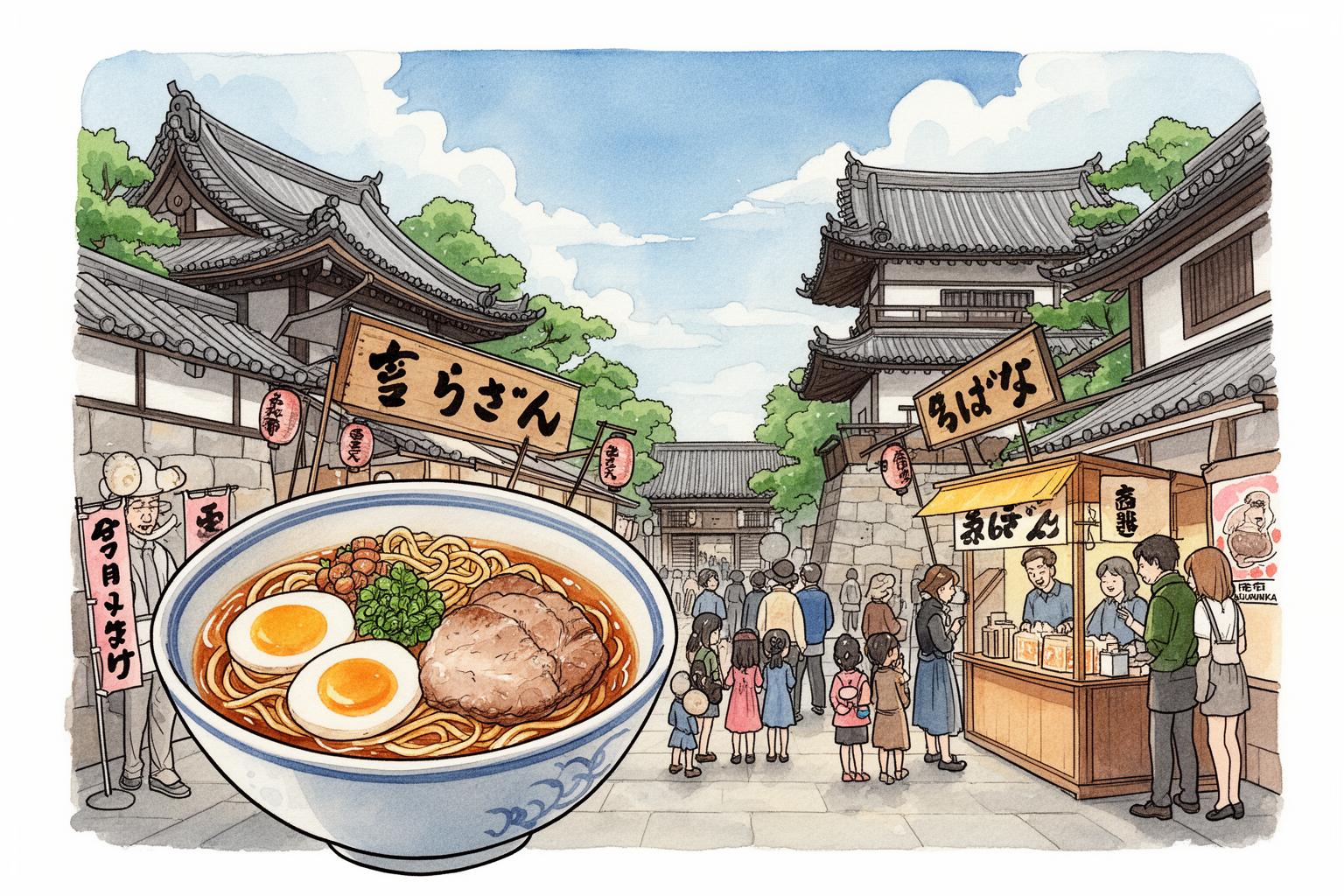

Let’s get the main event out of the way first, because it truly is a life-changing experience. Hakata-style tonkotsu ramen is Fukuoka’s soul served in a bowl. This isn’t your ordinary noodle soup. The broth steals the spotlight—rich, opaque, and creamy, crafted from simmering pork bones for hours, sometimes even days, to unlock all their collagen and savory richness. The result is a soup with mind-blowing depth of flavor. It’s savory, subtly sweet, and coats your mouth in pure umami lusciousness. Seriously addictive. Then there are the noodles—usually ultra-thin, straight, and firm, designed to hold up against the hearty broth without turning mushy. This is where the famous noodle firmness levels come into play. Locals order using terms like ‘barikata’ (extra firm), ‘kata’ (firm), or ‘futsu’ (regular). Going ‘barikata’ is the ultimate pro move, delivering a satisfyingly chewy texture right through to the last slurp. And don’t overlook the ‘kaedama’ culture! When your noodles run low but your soup remains, you can order a refill for a small price. Game-changer. Toppings are simple yet essential: a few slices of melt-in-your-mouth ‘chashu’ (braised pork belly), a sprinkle of finely chopped green onions, crunchy ‘kikurage’ (wood ear mushrooms), and occasionally a sheet of nori. Many stalls offer condiments like ‘beni shoga’ (pickled red ginger), ‘karashi takana’ (spicy pickled mustard greens), and freshly crushed garlic so you can customize your bowl. Eating ramen at a yatai, with steam warming your face on a brisk night, is a memory in the making. It’s more than a meal; it’s a ritual.

Yakitori & Kushiyaki: Skewers Galore

Next up on the must-try list is the world of grilled skewers. Yakitori (chicken skewers) and Kushiyaki (a broader term for grilled skewers of meat and veggies) are perfect yatai fare. They’re easy to eat, endlessly varied, and taste a million times better when cooked over live charcoal right before your eyes. The taisho stands expertly over the grill, fanning flames and turning skewers with precision until they’re perfectly cooked and slightly charred. Usually, you can choose between two main seasonings: ‘shio’ (salt) for a clean, simple taste that highlights the ingredients, or ‘tare’ (a sweet and savory soy-based sauce) that caramelizes on the grill and is finger-licking good. The skewer menu is an adventure on its own. Classics like ‘momo’ (juicy chicken thigh), ‘negima’ (chicken and green onion), and ‘tsukune’ (savory chicken meatball) are staples. But the real fun lies in trying bold options like ‘kawa’ (crispy chicken skin), ‘sunagimo’ (chicken gizzard with a delightful crunch), or ‘hatsu’ (chicken heart). Beyond chicken, you’ll often find amazing pork skewers, such as ‘butabara’ (pork belly)—a huge Fukuoka favorite, fatty, succulent, and utterly delicious. There are also vegetable choices like shiitake mushrooms, green peppers, and ginkgo nuts. Ordering a few skewers alongside a cold beer or warm sake is the ideal way to start your yatai night. It’s a social food meant for sharing and savoring over great conversation.

Oden: The Ultimate Winter Comfort

If you visit Fukuoka when it’s cooler, you’ll inevitably be drawn to the captivating sight of a large, steaming pot of oden. Oden is the quintessential Japanese comfort food—a mix of various ingredients simmered long and slow in a light, flavorful dashi broth. It’s like a warm hug in a bowl. Looking into the oden pot, you see a beautiful mosaic of shapes and textures. The fun part is choosing what you want; just point, and the taisho plucks your selections from the broth, serving them with a bit of dashi and a dab of sharp ‘karashi’ (Japanese mustard) on the side. Oden all-stars include thick slices of ‘daikon’ (radish) soaked with broth until tender and flavorful, ‘tamago’ (hard-boiled egg) transformed by the dashi, fish cakes like ‘chikuwa’ and ‘hanpen’, tofu varieties such as ‘atsuage’ (deep-fried tofu), and the wonderfully gelatinous, healthy ‘konnyaku’ (konjac jelly). Each yatai has its own secret dashi recipe, so every oden experience is a little different. It’s humble simplicity at its best, with incredible depth of flavor—a perfect dish to savor slowly while soaking in the yatai atmosphere.

Gyoza & Mentaiko: Local Favorites Not to Miss

Beyond the big three, yatai menus are filled with other delightful surprises that showcase Fukuoka’s unique food culture. Keep an eye out for ‘hakatateki gyoza’—small, bite-sized pan-fried dumplings arranged in a circle and fried until their bottoms turn irresistibly crispy and golden, while the tops stay soft and juicy. They’re insanely addictive, and you’ll find yourself ordering a second plate before finishing the first. Another Fukuoka specialty you must try is ‘mentaiko’ (marinated pollock roe), known for its salty, spicy, and savory flavor that’s uniquely Japanese. At yatai, you may find it served simply grilled or used in dishes like ‘mentaiko tamagoyaki’ (rolled omelet filled with mentaiko). The pairing of fluffy, slightly sweet egg and spicy, savory roe is heavenly. Exploring these other dishes adds to the fun; you might find tempura, stir-fries, or even French-inspired offerings at some of the more modern yatai. The rule of thumb: if it looks and smells good, just point and order. You won’t regret it.

Yatai Etiquette 101: How to Vibe with the Locals

Alright, so you’re ready to dive in but want to do it right and avoid looking like a total tourist newbie. Perfect. Knowing a few basic rules of yatai etiquette will make your experience smoother and show respect for the culture. It’s pretty simple, so no need to stress.

First off, yatai are small. Like, really small. Seating is very limited, usually just a counter with around 8-10 spots. Because of this, it’s not a place to camp out all night. The general idea is to order, eat, have a drink or two, and then move on to let others have a turn. Think of it as a fun, quick stop during a longer night out, not the main destination. This rotation keeps the energy lively. When you find a stall you like, don’t just squeeze in. Make eye contact with the taisho and ask if it’s okay to sit or gesture to an empty seat. A simple “Ii desu ka?” (Is this okay?) works wonders. Once seated, don’t take up extra space with your bags—tuck them under your stool or keep them on your lap. Remember, you’re sharing a cozy space.

Ordering is typically straightforward. Most yatai have menus posted, but they might only be in Japanese. Don’t worry! That’s part of the adventure. You can always point to what looks good. Spot something tasty on the grill or see what the person next to you is eating? Just point and say “Kore kudasai” (This one, please). The taisho and other customers are usually friendly and happy to help. One important thing to know is that each person is generally expected to order at least one drink and one food item. Yatai make their money on volume, so just sitting for a glass of water isn’t the way to go.

When your food arrives, it’s all about enjoying the moment. Strike up a conversation with your neighbors! A simple “Oishii!” (Delicious!) can open the door. Ask for their recommendations. This is how you get the best local tips and maybe even make some new friends. The taisho is often the heart and soul of the stall and a good character. If they’re not too busy, chatting with them is part of the fun. But be mindful of their workflow; they’re managing both kitchen and front-of-house in a tiny space on wheels. It’s an impressive feat of multitasking.

When it’s time to pay, it’s usually cash only, so make sure you have some yen. They’ll typically tally your bill on a small notepad or abacus. It’s not the place to split bills among a big group, so it’s easier if one person pays and you settle up afterward. There’s no tipping in Japan, so the price you see is the price you pay. When you’re finished, say a warm “Gochisousama deshita!” (Thank you for the meal!), a polite way to signal you’re done. By following these simple tips, you’re not just being a respectful guest—you’re actively engaging in the culture of yatai, which centers on community, consideration, and a shared love of good, honest food.

Not Just Nakasu: Exploring Tenjin and Nagahama

While Nakasu shines as the dazzling, postcard-perfect emblem of Fukuoka’s yatai culture, it certainly isn’t the only option. True insiders know that each district offers its own distinct vibe and character. Exploring beyond Nakasu’s main strip reveals diverse atmospheres and unique culinary delights. It’s time to discover the holy trinity of Fukuoka’s yatai neighborhoods: Nakasu, Tenjin, and Nagahama.

Tenjin: The Shopper’s Haven with a Food Lover’s Heart

Tenjin serves as Fukuoka’s vibrant downtown center, a focal point for shopping, fashion, and business. By day, the scene revolves around department stores and chic boutiques. But as night falls, tucked away on side streets and near major banks, yatai emerge, providing a delicious refuge for tired shoppers and office workers alike. The yatai in Tenjin—especially around the Bank of Japan and along Showa-dori—feel more seamlessly woven into the city’s urban fabric. Here, you might enjoy a bowl of ramen while watching late-night commuters rush past. The atmosphere is less touristy and more attuned to locals. The selection of stalls is excellent: some are traditional, run by families for generations serving classic Hakata comfort food, while others are modern and inventive, led by younger chefs putting creative twists on classics. You might find yatai offering French dishes like escargot or imaginative tempura. This area perfectly showcases the evolving yatai culture. Being a major transport hub, Tenjin is incredibly accessible. Sampling several yatai after a day of shopping makes for an ideal Fukuoka evening. The crowd is diverse, the food outstanding, and it feels like uncovering the city’s delicious secret hidden in plain sight.

Nagahama: The Ramen Original Gangster’s Favorite

For true ramen enthusiasts, a pilgrimage to Nagahama is essential. Situated near the city’s fish market, this neighborhood is widely regarded as the birthplace of Nagahama-style ramen—a close kin and arguably a predecessor to the more famous Hakata ramen. The yatai here possess a markedly different atmosphere compared to Nakasu’s polished stalls. They’re grittier, no-frills, and carry a working-class, old-school charm that feels incredibly genuine. The focus is less on scenic river views and more on the serious business of savoring some of the best noodles you’ll ever taste. Nagahama ramen is known for its ultra-thin noodles and a lighter but richly flavorful tonkotsu broth. This tradition began as a quick way to feed the busy fish market workers, explaining the thin noodles (which cook fast) and the widespread use of the ‘kaedama’ noodle refill system. Nagahama’s stalls are legendary, opening early and often staying late to serve the market crowd. You won’t find a large variety of foods here; the spotlight is firmly on ramen, and it’s perfected. Dining on ramen in Nagahama feels like tapping into the fundamental core of Fukuoka’s culinary identity—raw, delicious, and utterly unforgettable for any serious noodle lover.

The History & Culture: Why Yatai are So Legit

To truly appreciate what you’re experiencing when you squeeze into a yatai stall, you need to understand that this isn’t some new, trendy pop-up concept. Yatai are a living, breathing part of Japanese history, especially Fukuoka’s post-war narrative. Their origins trace back to the period immediately following World War II. During a time of scarcity and rebuilding, these mobile food stalls emerged as a vital service, offering affordable, hot meals to workers reconstructing the city. They stood as symbols of resilience, community, and entrepreneurial spirit. At their height, hundreds of yatai dotted Fukuoka, each serving as a small beacon of warmth and nourishment.

Yet, the story of yatai is also one of endurance. Over time, stricter regulations around hygiene, traffic, and public spaces caused their numbers to plummet. For years, the city halted the issuance of new licenses, so when a taisho retired, their stall and license vanished forever. The yatai culture, so integral to Fukuoka’s identity, was at risk of disappearing. The community of stall owners, known as the ‘yatai-gumi,’ along with local supporters, fought persistently to safeguard this unique cultural treasure. They recognized that yatai were more than just dining spots; they were essential community hubs, ‘shako-ba’ (socializing places) where people from all walks of life could come together. They were the original social network, long before the internet.

Acknowledging their significance to the city’s tourism and cultural heritage, the Fukuoka city government eventually updated its policies. In recent years, a new public application system for yatai licenses was introduced to preserve the tradition while upholding high standards of safety and hygiene. This has revitalized the scene, enabling a new generation of passionate chefs to open their own stalls, bringing innovative ideas and energy while honoring past traditions. So, when you sit at a yatai today, you become part of this rich and captivating story. You support a small, independent business owner who is upholding a valuable cultural tradition. Every bowl of ramen, every grilled skewer, carries the history of resilience and community. It’s a connection to the city’s soul that you simply won’t find in a typical restaurant. This deep cultural backdrop is what makes the yatai experience so profound and meaningful — a taste of history served with legendary hospitality.

A Deep Dive into Hakata Ramen: The Anatomy of a Perfect Bowl

We’ve touched on it and praised it, but to truly grasp Fukuoka, we must examine Hakata ramen closely. This is more than just a dish; it’s a science, an art form, and a cultural passion. Analyzing its fundamental elements reveals why it has won the hearts and appetites of people globally. It’s a brilliant example of how simple ingredients, handled with great care and respect, can produce something truly exceptional.

The Soup: Porky Perfection

The foundation, heart, and soul of Hakata ramen is the ‘tonkotsu’ broth. The term literally means ‘pork bone,’ which is the central essence of the recipe both literally and spiritually. The process demands patience and affection. Pork bones—femurs, knuckles, and more—are meticulously cleaned and boiled at a vigorous, rolling boil for a long duration. We’re talking at least 8 to 12 hours, and some renowned shops maintain a continuous process that lasts days, adding fresh bones and water to a ‘mother soup.’ This high-heat, intense cooking is essential. It doesn’t merely create stock; it emulsifies the fat and dissolves collagen and marrow from the bones into the broth. This results in the soup’s characteristic milky, opaque look and its rich, creamy, luscious texture. The aroma is strong and distinctly porky—a scent that ramen aficionados find irresistible. Though rich, a well-crafted tonkotsu broth shouldn’t feel heavy or greasy. It should be deeply savory with a delicate sweetness and complex, lingering flavor. Each yatai and ramen shop has its unique recipe, a special formula of bones, aromatics, and cooking time that defines their broth. This soup is the product of decades of tradition and is truly one of Japan’s culinary masterpieces.

The Noodles: Katamen Culture

If the broth is the soul, the noodles are the backbone. Hakata ramen noodles are as distinctive as the broth itself—thin, straight, and made from low-hydration dough. This means less water is used in making the noodles, producing a firmer, less elastic texture with a slight snap. This type of noodle serves two main purposes. First, its thinness allows very quick cooking, ideal for feeding busy market workers originally. Second, its firmness perfectly complements the rich, creamy broth by absorbing its flavor without becoming soggy or limp. This brings us to the ‘katasa’ (firmness) scale. When ordering, you control your noodle texture: ‘Yawa’ (soft) for a tender bite, ‘Futsu’ (regular) as the standard, ‘Kata’ (firm) for an al dente feel, and then ‘Barikata’ (extra firm) and ‘Harigane’ (wire-like) for noodle purists who want maximum chewiness. The culture of ‘kaedama’ (noodle refill) arose directly because of these quick-cooking, thin noodles. One serving may not be enough, and they’re best eaten promptly before softening. Ordering a kaedama delivers a fresh, perfectly cooked second batch into your remaining soup—offering a second round of ramen brilliance. Pure genius.

The Toppings: What’s Your Combo?

While the soup and noodles take center stage, the toppings are the critical supporting ensemble that completes the dish. Hakata ramen toppings tend to be minimalist, designed to enhance rather than overshadow the broth. The most popular and cherished topping is ‘chashu,’ thin slices of pork belly slow-braised in a sweet-salty blend of soy sauce, mirin, and sake until meltingly tender. A good piece of chashu will literally dissolve in your mouth. ‘Negi’ (green onions) usually appear, adding a fresh, sharp, aromatic bite that cuts through the pork richness. ‘Kikurage’ (wood ear mushrooms) are another classic topping, thinly sliced to bring a delightful crunch and slightly gelatinous texture that deepens the bowl’s sensory experience. Other common additions include ‘menma’ (seasoned bamboo shoots), ‘nori’ (dried seaweed), or a soft-boiled egg (‘ajitama’). Customization continues at every yatai and ramen shop counter where a trio of essential condiments awaits to tailor your bowl precisely to your liking. ‘Beni shoga’ (pickled red ginger) provides a tangy, acidic kick. ‘Karashi takana’ (spicy pickled mustard greens) adds a salty, spicy punch. A clove of fresh garlic, crushable at your table with a press, delivers a sharp, aromatic burst. Experimenting with these is part of the joy and key to finding your perfect Hakata ramen bowl.

Practical Slay: Your Fukuoka Yatai Game Plan

Feeling hyped? Bet. To make sure your yatai adventure is a total win, here’s the lowdown on the practical side of things. A bit of prep will help you navigate the scene like a local pro and concentrate on what really matters: the food and the vibes.

Best Time to Go

Yatai come alive at night. They usually start setting up around sunset, typically between 5:00 PM and 6:00 PM, and are generally open for business by 6:30 PM or 7:00 PM. The peak hours are usually from about 8:00 PM to 11:00 PM, when the streets are lively and the stalls are busy. That’s when the atmosphere feels most electric. Most yatai stay open until at least 1:00 AM, with some going even later, making them perfect for a late-night meal after a few drinks. If you want to dodge the biggest crowds, try going right when they open or later in the evening after the initial rush has settled. Keep in mind that many yatai close one day a week (often Sunday or Monday), and they’ll shut down if the weather turns nasty, like during typhoons or heavy rain. Always have a backup plan, but on a clear night, you’re set.

Getting There

Fukuoka is super easy to get around, with the main yatai areas all centrally located and well-serviced by public transport. For the Nakasu area, the closest subway station is Nakasu-Kawabata Station, on the Kuko (Airport) and Hakozaki lines. From there, it’s just a short 5-minute walk to the riverfront, where the main yatai stretch is. For the Tenjin area, hop off at Tenjin Station (Kuko Line) or Tenjin-Minami Station (Nanakuma Line). The yatai dot the streets around major department stores and office buildings here. The Nagahama area is a bit farther on foot; the nearest subway stop is Akasaka Station (Kuko Line), about a 10-15 minute walk toward the port. Alternatively, you can catch a bus from Tenjin or Hakata Station, which might bring you closer. Taxis are plentiful and fairly affordable for short rides between these spots.

What to Wear

There’s no dress code at yatai. The vibe is very casual and laid-back. Comfort is key. Wear comfortable shoes since you’ll likely do some walking as you explore different stalls. In the cooler months, from late autumn to early spring, layer up. Although the grill’s heat and stall warmth provide some coziness, you’ll be sitting semi-outdoors, and it can get chilly. A warm jacket, scarf, and hat are wise choices. In summer, it can get hot and humid, so opt for light, breathable clothing. One practical tip: avoid wearing your best or easily stained clothes. You’ll be in close quarters, slurping soupy noodles and eating saucy skewers. Splashes happen, so it’s best to wear something you’re okay with getting a little food love on.

Budgeting Your Bites

Yatai are generally very affordable, which is part of their charm. They offer a fantastic and filling meal without breaking the bank. As a rough guide, a bowl of ramen usually costs between 700 and 1000 yen. Skewers typically run from 150 to 300 yen each. A plate of gyoza might be around 500 yen. Drinks like beer or sake tend to be about 500 to 700 yen. You can have a satisfying meal and a drink for roughly 2000 to 3000 yen per person. If you plan to hop between stalls and try a variety of dishes, budget a little more. The most important tip is to bring cash. Almost all yatai are cash-only. While Japan is growing more card-friendly, the yatai scene is still a place where old-school cash rules. Make sure you have enough yen ready to cover your foodie adventure. This simple prep will keep your focus on the amazing food and unforgettable atmosphere.