Yo, what’s the deal? It’s Daniel. Tonight, I’m trading my usual quiet mountain passes for a different kind of landscape—one painted in neon, steam, and the warm glow of paper lanterns. We’re diving headfirst into the heart of Fukuoka, into the very soul of Hakata: the legendary yatai scene. If you think street food is just a quick bite, you’re about to get your mind blown. This isn’t just about food; it’s about connection, it’s about history, and honestly, it’s a whole mood. Hakata’s yatai, these pop-up food stalls that materialize as dusk settles over the city, are more than just a place to eat. They are the city’s fleeting, open-air living rooms, where strangers become friends over sizzling skewers and bowls of life-changing ramen. This is where the city’s pulse is most palpable, a nightly festival of flavor and fellowship that you won’t find anywhere else in Japan on this scale. It’s raw, it’s real, and it’s absolutely unmissable. Bet. So, grab a seat, ’cause class is in session. We’re about to unpack why this incredible cultural experience is a must-do on any real Japan itinerary.

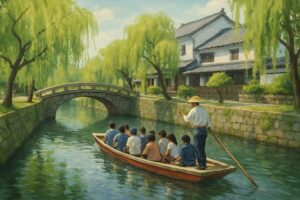

While the yatai offer an unforgettable street-level feast, for a completely different but equally essential Fukuoka experience, consider a serene journey through Yanagawa’s famous waterways.

The Yatai Vibe: More Than Just a Meal

Let’s clear one thing up right away: a yatai is not a restaurant. It’s an entirely different experience. Forget private tables, quiet conversations, and lengthy menus. This experience is defined by its charming limitations. Imagine this: a small wooden cart, skillfully unfolded and set up within hours, topped with a canvas roof and surrounded by a few stools. Maybe ten seats at most, packed shoulder-to-shoulder around a counter that serves as the kitchen. Inside this cozy space, the taisho—the owner, chef, and heart of the operation—conducts a symphony of sizzling, chopping, and pouring. The air is thick with the irresistible aroma of grilled pork belly, simmering dashi broth, and the subtle, sweet hint of sake. Lanterns cast a warm, cinematic glow, illuminating faces caught in brief moments of laughter and conversation. It’s noisy, a bit smoky, and absolutely magical. The energy is electric, a shared buzz ignited by great food and close quarters. Here, you’re not simply a customer; you become a temporary member of a small, fleeting community. You might find yourself chatting with the salaryman on your left about his day, or sharing a laugh with the couple from Osaka on your right. The taisho often takes center stage, remembering regulars, teasing newcomers, and fostering an atmosphere that’s irresistibly welcoming. This intimacy is the secret ingredient. In a world of digital detachment, the yatai offers a wholly analog experience. It compels you to be present, to engage with those around you and the place itself. It’s an energy that’s both vibrant and quietly comforting. Honestly, it’s one of the most genuine Japanese experiences you can have.

A Quick History of Hakata’s Rolling Kitchens

These seemingly simple food stalls are actually steeped in a deep and intricate history. The yatai culture in Fukuoka didn’t simply emerge overnight; it was born out of necessity. In the post-World War II era, as Japan worked to rebuild, resourceful entrepreneurs took to the streets. They assembled mobile carts to sell affordable, hearty dishes like ramen and yakitori to the working class, providing not only nourishment but also a sense of normalcy and community during difficult times. These modest stalls became crucial social hubs, nurturing the city’s spirit back to health. For decades, the yatai thrived, becoming an iconic symbol of Hakata’s resilience and culinary identity. However, their future was not always secure. In the mid-20th century, stricter regulations and sanitation concerns sparked a crackdown on street vending nationwide. Fukuoka became one of the few places where yatai culture was permitted to continue, but under strict controls. For many years, a rule was enforced that a yatai license could not be transferred, so when an owner retired, their stall vanished forever. This caused a gradual and melancholy decline in the number of yatai, falling from over 400 at their peak to just over 100. It seemed as though a cherished piece of the city’s heritage was slowly disappearing. Yet, the people and government of Fukuoka understood the value of what they had. Aware of the cultural and economic significance of the yatai, the city launched an innovative initiative in recent years. They introduced a new public application system, allowing enthusiastic new chefs to apply for licenses and open fresh stalls. This effort not only stopped the decline but also infused the scene with renewed energy and creativity. Today, you’ll find a new generation of taisho alongside seasoned veterans, preserving traditional flavors while also experimenting with new dishes, from French-inspired fare to craft cocktails. This revival stands as a testament to Fukuoka’s dedication to its living culture, ensuring the yatai remain not just a relic of the past but a vibrant, evolving part of its future.

The Three Realms of Yatai: Navigating the Zones

While yatai are spread across Fukuoka, they tend to concentrate in three main areas, each offering its own unique character and flavor. Understanding the differences is essential for crafting your ideal yatai-hopping experience. Think of these areas as different game levels, each presenting a distinct challenge and reward.

Nakasu: The Neon-Soaked Main Stage

This is the big one—the spot you’ve likely seen in countless photos. Located on the island of Nakasu, nestled between two rivers, this strip of yatai is the most famous and visually striking. As night falls, the stalls light up with warm lanterns reflecting on the water, set against the dazzling, neon-lit backdrop of the Nakasu entertainment district. The atmosphere here is vibrant and international. You’ll hear a mix of languages as tourists and locals converge on this iconic location. It’s sensory overload in the most exhilarating way. The stalls are generally a bit larger here, with more varied menus designed to appeal to a wider audience. While some purists may label it touristy, there’s no denying the spectacular show it offers. Photographing the yatai along the Naka River is a quintessential Fukuoka experience. For first-timers, Nakasu is an excellent introduction—easy to find, buzzing with energy, and offering a perfect glimpse into the yatai scene. Expect crowds, especially on weekends, and consider strolling the entire strip first to soak up the atmosphere and choose the stall whose vibe and menu draw you in.

Tenjin: The Urban Oasis

If Nakasu is the main stage, Tenjin feels like the cooler, more local backstage lounge. Situated in the heart of Fukuoka’s premier shopping and business area, the yatai here cater to a slightly different crowd. As department stores and offices close, shoppers and workers spill into the streets seeking a casual, tasty way to end their day. These stalls often nestle near major roads like Watanabe-dori, tucked close to department store and bank entrances. The vibe is less tourist-centric and more seamlessly woven into daily urban life. It feels more authentic—you’re just as likely to find yourself seated next to coworkers unwinding after work or a couple taking a break from shopping. The food consistently maintains high quality, with many long-established stalls serving loyal regulars for decades. Tenjin’s yatai offer a fantastic spot for people-watching and absorbing the pulse of everyday life in Fukuoka. Visiting here feels like finding a well-kept secret—a welcoming refuge of warmth and flavor tucked amid the city’s concrete and glass.

Nagahama: The Ramen Pilgrim’s Holy Land

For true food lovers, history enthusiasts, and ramen aficionados, Nagahama is sacred ground. Located near the city’s fish market, this area is the birthplace of Nagahama-style ramen, a distinct variation of the more famous Hakata ramen. The yatai here are the originals—guardians of a culinary legacy. The atmosphere is grittier, no-frills, and laser-focused on one goal: perfect noodles. Nagahama ramen is known for its extremely thin, firm noodles served in a lighter yet richly flavorful tonkotsu broth. These stalls were originally set up to serve busy fish market workers who needed quick, affordable, and satisfying meals. This history is why the concept of kaedama—a noodle refill—is central to the Nagahama experience. You start with a small portion of noodles to keep them from getting soggy and then call out for refills as many times as you want. While the Nagahama yatai area is less scenic than Nakasu and less bustling than Tenjin, it is a must-visit for any culinary pilgrim. It offers a taste of history and a direct connection to the origins of Fukuoka’s most famous dish. Visiting a Nagahama yatai feels less like a night out and more like paying homage at a temple of ramen.

The Yatai Menu Decoded: What’s Good, For Real

Alright, let’s dive into the delicious details. The menu at a yatai is typically small and focused, featuring a curated selection of dishes that the taisho has perfected. While each stall boasts its own specialties, certain standout items truly capture the Hakata yatai experience. Let’s explore the must-try dishes.

Hakata Tonkotsu Ramen: The Unrivaled Favorite

When in Hakata, eating tonkotsu ramen at a yatai is essential. It’s a foundational experience and more than just noodle soup—it’s an art form. The broth, or tonkotsu, is the centerpiece, made by boiling pork bones for hours or even days until they release collagen and marrow, creating a broth that’s incredibly rich, creamy, and opaque white. Its flavor is deep, complex, savory, and utterly soul-satisfying. Swimming in this magical broth are noodles that are characteristically thin, straight, and firm, providing a perfect textural contrast to the silky soup. Typical toppings are simple yet essential: a few slices of tender chashu (braised pork), chopped green onions, and perhaps pickled ginger or sesame seeds. Slurping a bowl of this ramen on a cool night, steam rising into the air, is pure bliss. And don’t forget the kaedama tradition: finishing your noodles and calling out for a refill is part of the ritual—a true rite of passage.

Yakitori and Kushiyaki: Mastering the Skewer

A key element of the yatai menu is anything grilled on a stick. Yakitori technically refers to grilled chicken but is often used interchangeably with kushiyaki, which includes a variety of skewered and grilled delights. The undisputed champion in Fukuoka is butabara, grilled pork belly. These succulent fatty strips are perfectly grilled, simply seasoned with salt (shio), and often served with a dab of mustard. It’s a local favorite for good reason. Beyond pork belly, the choices are vast, including classics like negima (chicken and leek), tsukune (chicken meatballs), and more adventurous options like kawa (crispy chicken skin) and reba (liver). The beauty lies in the simplicity: high-quality ingredients cooked over charcoal, which infuses a smoky flavor that’s irresistible. Usually, you can choose between salt (shio) or a sweet and savory soy-based glaze (tare). Ordering several different skewers alongside a cold beer is the ideal way to start your yatai night.

Oden: The Ultimate Comfort Dish

When the temperature drops, the sight of a simmering pot of oden is deeply comforting. Oden is a type of Japanese hot pot where a variety of ingredients gently simmer in a light, savory dashi broth. Each yatai’s broth is its own secret recipe and a point of pride for the taisho. The fun of oden is selecting what you want from the communal pot. Staple items include wobbly, broth-soaked daikon radish, triangles of atsuage (fried tofu), jiggly blocks of konnyaku (konjac jelly), perfectly boiled eggs, and a wide variety of nerimono (fish paste cakes) in diverse shapes and sizes. It’s served with a smear of sharp karashi mustard. Oden is like a warm hug in food form—subtle, deeply satisfying, and a wonderful way to experience a different dimension of Japanese flavors. It’s the perfect dish to savor slowly while you chat and soak up the atmosphere.

Gyoza and Motsunabe: Local Treasures

Beyond the big three, many yatai offer other Fukuoka specialties that are definitely worth seeking out. One of these is hitokuchi gyoza, or one-bite dumplings. Unlike the larger gyoza you might know, these are small, delicate parcels filled with minced pork and vegetables, pan-fried to achieve a super crispy, golden-brown bottom while the top remains soft and steamed. They’re dangerously addictive and pair perfectly with a cold drink. For the more adventurous, you must try motsunabe, a Fukuoka-style hot pot made with motsu, which is beef or pork offal. Before you get squeamish, hear me out: the offal is simmered in a flavorful broth (typically soy sauce or miso-based) with cabbage, chives, and garlic. The resulting dish is incredibly rich and packed with collagen. It’s a genuine local soul food beloved by Fukuoka residents, and trying it at a yatai offers an authentic, next-level experience.

Yatai Etiquette 101: How to Vibe Like a Local

To fully appreciate the yatai experience, it’s helpful to know the unspoken rules of engagement. This isn’t about strictness; it’s about honoring the culture and ensuring a smooth, enjoyable time for yourself, your fellow diners, and the dedicated taisho. Adhering to this simple etiquette will have you blending in like a seasoned pro.

- Don’t Linger: This is the key rule. Yatai offer very limited seating, and there’s often a queue waiting. The culture encourages eating, drinking, and moving on. Think of it as a sprint, not a marathon. Typically, you have a drink or two and a few dishes within about an hour, then make way for the next guest. It’s common to “yatai-hop,” visiting two or three stalls in one evening to enjoy various foods and atmospheres.

- Wait to Be Seated: Never just sit down in an empty spot. Always make eye contact with the taisho and wait for them to acknowledge you and show you where to sit. They expertly manage seating flow in a very tight space.

- Order Promptly: Once seated, quickly glance at the menu (often on the wall) and be ready to order. Starting with just a drink and one or two dishes is perfectly fine. You can always order more later. If unsure, ask the taisho for a recommendation (osusume wa?) or simply point to what the guest next to you is having.

- Cash is King: Although Japan is becoming more card-friendly, yatai mostly operate on cash. Assume cards aren’t accepted. It’s best to carry small bills and coins. When paying, don’t request to split the bill; one person should pay for the entire group.

- Embrace the Community: The close quarters are an invitation, not a barrier. Feel free to start a conversation with the person next to you. A simple “kanpai!” (cheers!) can spark a memorable exchange. Chatting with locals and the taisho is a big part of the fun.

- Keep it Clean: Space is limited. Keep your bags and belongings tucked away so they don’t obstruct others. Be mindful of your elbows and personal space. It’s a delicate balance, but everyone manages it with surprising grace.

Through a Photographer’s Lens: Capturing the Yatai Night

As a photographer, the yatai scene is a dream come true. It’s a tough setting—dim light, constant movement, tight spaces—but the rewards are tremendous. The potential for visual storytelling is exceptional. The key is to capture the atmosphere, not just the food. Pay attention to the light: how the warm glow of a single paper lantern illuminates steam rising from a bowl of ramen or catches the sparkle in someone’s eye as they laugh. Use a fast lens (a wide aperture like f/1.8 or f/2.8) to maximize light intake and create that soft background blur that makes your subject stand out. Notice the small details: the taisho’s weathered hands skillfully flipping skewers, the intricate designs on the oden pot, the condensation on a chilled glass of beer. Capture the interactions—a quiet chat between friends, the lively cheers of a group of salarymen, the chef’s focused expression. These human moments tell the true story. Always remain respectful. A yatai is an intimate space, not a public photo studio. Be subtle. Avoid using flash, as it disrupts the atmosphere and disturbs everyone. When taking close-ups of the taisho or another customer, a simple smile and a nod toward your camera usually suffice to ask permission. The beauty of the yatai lies in its fleeting nature. It operates only a few hours each night before disappearing. Your photos can preserve a piece of that transient magic.

Planning Your Yatai Pilgrimage: The Nitty-Gritty

Ready to get started? A bit of planning can greatly enhance your yatai experience, making it smooth and enjoyable. Here’s the essential information you need to know.

- When to Go: Yatai usually open around 6:00 or 7:00 PM and stay open late, often past midnight. They are typically closed on Sundays and during bad weather (heavy rain or typhoons). Weeknights are generally quieter and attract more locals, making it easier to find a seat. Friday and Saturday nights are the busiest, with a lively, festive atmosphere, but expect to wait for a spot.

- Getting There: Fukuoka’s public transportation is very convenient. For the Nakasu area, the nearest subway station is Nakasu-Kawabata on the Kuko and Hakozaki lines. For the Tenjin area, Tenjin Station (Kuko Line) or Tenjin-Minami Station (Nanakuma Line) will place you right in the center of the action. For the Nagahama area, it’s a bit of a walk; Akasaka Station (Kuko Line) is closest, followed by about a 15-minute walk toward the port.

- What to Wear: Dress casually and comfortably. You’ll be sitting on simple stools, and the air can get smoky from the grills, so avoid your finest clothes. During colder months, be sure to layer up since you’ll be seated outdoors.

- Budgeting: Yatai aren’t necessarily the cheapest option, but they offer excellent value through the experience. You’re paying for the food, atmosphere, and personalized service. Expect to spend around 2,000 to 4,000 yen per person for a few drinks and dishes. Ramen typically costs between 600 and 900 yen, while skewers are usually 150 to 300 yen each.

- Going Solo vs. With a Group: Yatai are ideal for solo travelers. The counter seating encourages interaction, making it easy to join conversations. For groups, it’s best to stay small—two or three people can usually be seated together, but larger groups will have difficulty since yatai are not designed for big parties.

More Than a Meal, It’s a Memory

As the night winds down and the taisho carefully begins dismantling their stall, packing away a world of flavor and community until the next evening, you’re left with more than just a full stomach. You depart with a sense of connection. You’ve shared a space, a laugh, and a meal with complete strangers, breaking down the barriers that often exist in a big city. The Hakata yatai serve as a powerful reminder that the most meaningful travel experiences are often the simplest: good food, warm light, and the company of others. They are the beating heart of this remarkable city, a living, breathing piece of cultural heritage that welcomes you in and makes you feel, if only for one night, like a local. So when you visit Fukuoka, don’t just observe the yatai from afar. Be bold. Pull back the canvas flap, find an empty stool, and take a seat. You’re not merely ordering dinner; you’re stepping into the story of Hakata. And believe me, it’s a story you’ll want to be part of. Peace.