There are places in Japan that feel less like destinations and more like living poems. They unfold not on a map, but in the rhythm of a boatman’s song, in the scent of charcoal smoke curling over water, and in the deep, comforting warmth of a meal perfected over centuries. Yanagawa, a small city nestled in the southern reaches of Fukuoka Prefecture, is one such poem. Known as the ‘City of Water,’ it is a place woven from a web of canals, a liquid labyrinth that has shaped its history, its culture, and its very soul. To drift through Yanagawa is to drift through time, under weeping willows and impossibly low bridges, propelled by the gentle push of a bamboo pole. But this journey, as beautiful as it is, is truly a pilgrimage towards a singular culinary revelation: Unagi no Seiro-mushi, steamed eel on rice. This isn’t just a local specialty; it’s the heart of Yanagawa, a dish so intrinsically linked to the landscape that to taste it is to understand the city itself. It’s a story served in a steaming cypress box, a testament to the slow, patient artistry that flows as surely as the water in the canals.

To fully appreciate this culinary pilgrimage, one must understand the deep connection between Yanagawa’s famous steamed eel and its unique waterways, which you can explore further in our guide to Yanagawa’s unagi and canals.

The Liquid Soul of a Castle Town

To truly understand Yanagawa, you must first understand its water. The canals, locally called horiwari, are far more than decorative features. They form the city’s circulatory system—a network of arteries and veins carved centuries ago. This story starts with the building of Yanagawa Castle in the 16th century. These waterways were originally designed as a strong defensive moat, a strategic barrier of water and mud. Over time, as peace prevailed, their role shifted. They became crucial for irrigation, nourishing the fertile Chikugo Plain and enabling agricultural prosperity. They also served as transportation routes, with boats ferrying goods and people, linking communities long before paved roads were common. This elaborate network, stretching about 470 kilometers, transformed Yanagawa into a vibrant castle town, its life and commerce governed by the water’s flow.

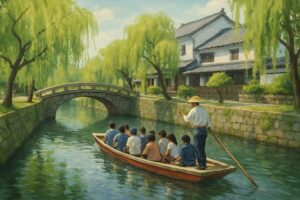

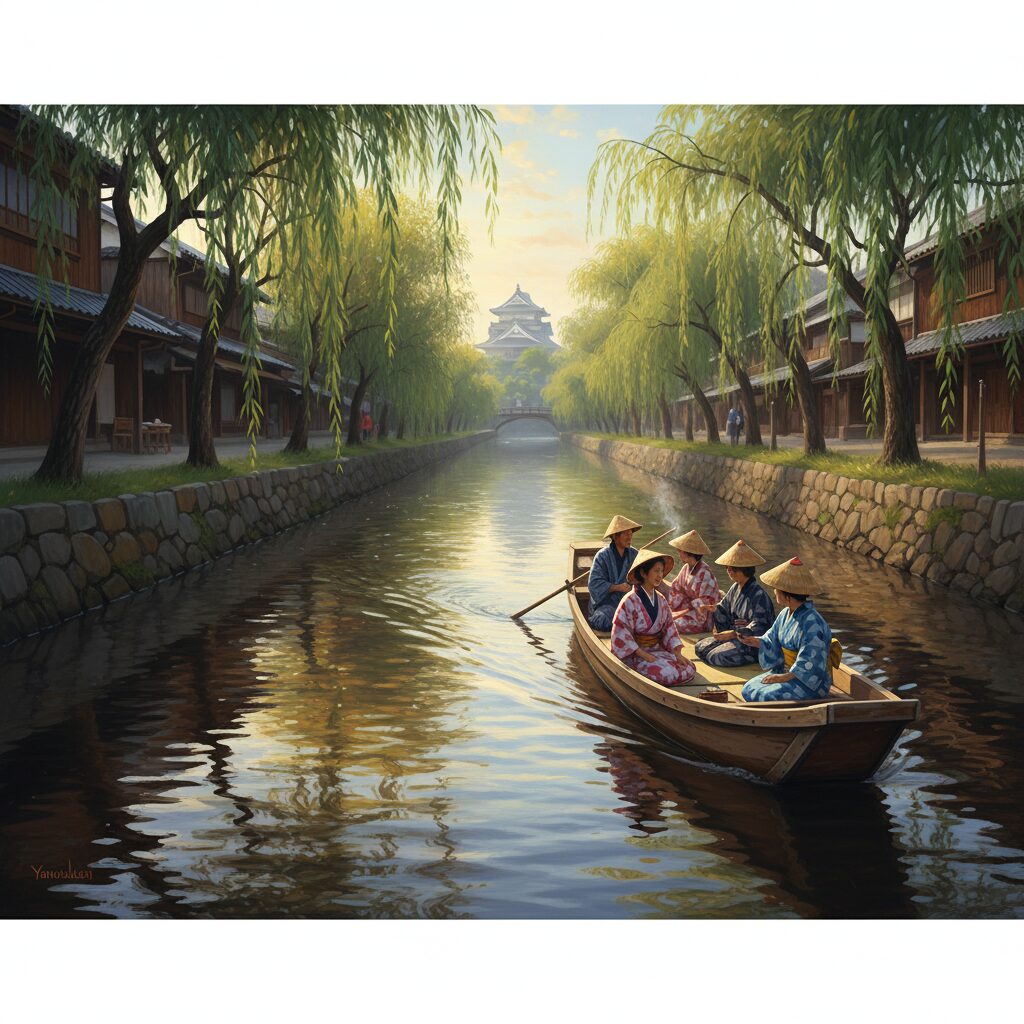

The Poetry of the Kawakudari

The quintessential Yanagawa experience is the kawakudari, or ‘going down the river.’ This is not a fast-paced tour; it is an education in the art of slowness. You settle yourself onto the floor of a long, narrow wooden boat called a donko-bune, and with a gentle push from your boatman, the sendo, the outside world begins to fade away. The only propulsion comes from the sendo’s strength and skill, as he skillfully guides the boat with a single long bamboo pole, its tip finding grip on the canal floor. The sounds are subtle yet immersive: the soft splash of the pole entering the water, the gentle lapping of waves against the hull, the rustle of willow branches brushing the boat’s roof.

The journey unfolds like a cinematic scene. You glide past the weathered wooden walls of old storehouses, their foundations dipping directly into the water. You pass the moss-covered stone walls of the old castle grounds, heavy with history. Traditional Japanese homes with carefully tended gardens appear, their residents occasionally waving as you go by. The route is a tapestry of textures and colors that shift with the seasons. In spring, cherry and plum blossoms create a canopy of pale pink and white, their petals drifting down onto the water’s surface. Early summer brings vibrant purple and blue iris flowers lining the banks in spectacular fashion. In autumn, the leaves of maple and ginkgo trees blaze in hues of crimson and gold, their reflections shimmering in the canal. Even winter offers a special charm, when the boats are transformed into kotatsu-bune, fitted with heated tables covered by thick quilts, allowing you to stay warm and cozy while drifting through the stark, quiet beauty of the dormant landscape.

But the kawakudari is more than sightseeing. It is a performance. The sendo, often dressed in traditional attire with a conical straw hat, is your guide, storyteller, and entertainer. With a voice carrying over the water, they share local history, point out landmarks, and recount amusing anecdotes. Many are renowned for their singing, performing folk songs and the poems of Kitahara Hakushu, Yanagawa’s most celebrated literary figure, whose verses were inspired by these very canals. Their songs echo beneath the bridges, creating moments of pure, heartfelt Japanese nostalgia. One of the most memorable parts of the cruise is navigating the numerous low-slung bridges. With a call of warning from the sendo, everyone on board must duck low as the boat slides through the narrow spaces, a thrilling and intimate experience that connects you closely to the town’s unique architecture.

The Art of Steam: Unagi no Seiro-mushi

The slow, winding boat ride provides the perfect introduction to the main event: Yanagawa’s culinary masterpiece. Long before reaching your destination, you’ll catch a whiff of it—a sweet, savory, smoky aroma that lingers in the air, embodying the very essence of unagi (freshwater eel) grilled over charcoal. While many places in Japan are renowned for eel, Yanagawa’s approach is distinctive. Here, the dish transcends the usual unadon or unajuu—grilled eel served over rice in a bowl or lacquer box. Instead, it is elevated to an art form known as Unagi no Seiro-mushi, or steamed eel.

Crafting this dish is a layered symphony of technique and flavor, showcasing the patience and precision central to Japanese cuisine. This tradition is believed to have begun in Yanagawa over 300 years ago, inspired by a desire to serve eel and rice piping hot to customers. The ingenious solution was steaming.

Deconstructing the Masterpiece

Seiro-mushi is presented in a rectangular steamer box made from cypress or bamboo, lending a subtle, woody fragrance to the dish. When the lid rises, a fragrant cloud of steam escapes, revealing a stunning culinary tableau. The surface is a mosaic of color and texture. Dark, glossy eel fillets, glazed with a rich, caramelized sauce, rest atop a bed of rice. Interspersed among the eel are delicate, paper-thin strands of golden omelet called kinshi tamago. This is no mere garnish; its mild sweetness and soft texture perfectly balance the eel’s rich intensity.

The preparation is exacting. First, the eel is filleted, deboned, and skewered. It is then grilled over white-hot charcoal without seasoning—a process called shirayaki. This initial grilling cooks the eel and renders out excess fat, producing a firmer texture. Next, the eel is steamed once to tenderize it. Finally, it is repeatedly dipped into a proprietary tare sauce—a closely guarded secret at each restaurant, typically a blend of soy sauce, mirin, sake, and sugar, often drawn from a mother pot replenished for decades—and then grilled again. This second grilling, known as kabayaki, caramelizes the sauce, creating its signature char and deep, savory flavor.

Yet the true magic of seiro-mushi lies in the final step. Rice, already mixed with some of the treasured tare sauce, is placed into the seiro box. The perfectly grilled eel fillets are arranged on top, and the entire box is set into a steamer. This last steaming sets the dish apart. The steam envelops everything, blending the flavors fully. The rice becomes fluffy and moist, infused with the smoky essence of eel and the umami of the sauce. The eel itself turns incredibly soft and tender, nearly melting in your mouth—a texture far more delicate than typical grilled eel dishes. Each grain of rice carries flavor, and every bite offers a harmonious fusion of smoky, sweet, savory, and earthy notes.

Accompanying the seiro-mushi is a small bowl of kimo-sui, a clear, elegant eel liver soup. The broth is a light dashi, subtly flavored, with the liver adding a unique, slightly bitter note that acts as a superb palate cleanser, cutting through the richness of the main dish and preparing you for the next satisfying mouthful.

The Sanctuaries of Eel

Yanagawa is dotted with unagi restaurants, many operated by families for generations. These are more than eateries; they are guardians of the city’s culinary heritage. Finding one is simple—just follow your nose. The two most celebrated names are Ganso Motoyoshiya and Wakamatsuya. Ganso Motoyoshiya claims to be the originator of the seiro-mushi style, boasting a history spanning over 300 years. Dining there feels like stepping back in time. You remove your shoes at the entrance and are led through wooden corridors to a tatami room, where you sit on cushions and gaze out at a tranquil Japanese garden while awaiting your meal. The atmosphere is calm and reverent. Wakamatsuya, located near the canal where many boat tours conclude, offers a similarly traditional experience, complete with stunning views of the water.

When ordering, you’ll typically see options like jo (superior) and toku-jo (extra superior), usually indicating the quantity of eel served. For first-timers, the standard portion is more than sufficient to savor the full experience. The arrival of the steaming box is a moment of theater. Don’t hurry. Take time to appreciate the steam, the aroma, the artistry before your first bite. It is a meal that demands your full attention, a slow, contemplative experience that reflects the unhurried rhythm of the city itself.

Beyond the Water and the Feast

While the canal cruise and the eel are undoubtedly the primary attractions, Yanagawa offers much more to those willing to explore its tranquil streets. The city’s rich history and cultural treasures provide a deeper understanding of the beauty you experience from the water.

Tachibana-tei Ohana

After your meal, a visit to the Tachibana-tei Ohana is a must. This was formerly the villa of the Tachibana clan, the feudal lords who governed the Yanagawa domain for centuries. Today, it serves as a splendid museum and garden complex, offering insight into the lavish lifestyle of the Japanese aristocracy. The property showcases a fascinating mix of architectural styles. The Seiyokan, a grand Western-style mansion built in 1910 to host dignitaries, presents an elegant contrast to the adjacent traditional Japanese buildings and expansive garden.

The centerpiece is the Shotoen garden, designated a National Site of Scenic Beauty. Designed to emulate the famous scenic bay of Matsushima, the garden features a large pond dotted with over 280 small islands and thousands of black pines. It is a masterpiece of landscape design, carefully maintained, with a path that lets you stroll around its perimeter and appreciate its beauty from every angle. The main hall of the Ohana villa contains a grand tatami room with verandas that open directly onto the garden, creating a seamless connection between the interior and the natural surroundings. Within the complex, you can also see a collection of the Tachibana family’s heirlooms, including samurai armor, exquisite lacquerware, and valuable documents.

The City of a Poet: Kitahara Hakushu

Yanagawa is also renowned as the birthplace of Kitahara Hakushu (1885-1942), one of modern Japan’s most cherished poets and writers of children’s songs. His work is deeply infused with the spirit of his hometown; the canals, willows, and rhythms of local life are recurring themes in his poetry. To engage with this literary heritage, you can visit his birthplace, preserved as a museum. Walking through the rooms of the old merchant-class house where he was raised, you can sense the environment that influenced his artistic sensibilities. The nearby Yanagawa Municipal History and Folklore Museum also houses extensive exhibits dedicated to his life and works. Understanding Hakushu’s bond with Yanagawa adds another dimension to the boatman’s songs and the poetic landscape around you.

Sagemon: The Festival of Hanging Dolls

If you are lucky enough to be in Yanagawa between mid-February and early April, you will see the city at its liveliest during the Yanagawa Hina-matsuri Sagemon Meguri. The Hina-matsuri, or Doll Festival, is celebrated throughout Japan on March 3rd to pray for the health and happiness of young girls. In Yanagawa, this festival includes a unique and spectacular tradition called sagemon. These are vibrant, handcrafted decorations made by mothers and grandmothers. Each sagemon consists of two large, colorful balls made of rolled silk, from which hang numerous strings adorned with small, symbolic charms. These charms, often numbering 51 to represent wishes for a long life, are crafted in shapes like auspicious animals such as cranes and turtles, fruits like peaches (symbolizing longevity), and other treasured objects. These intricate sagemon are displayed on either side of the traditional tiered doll stands in homes, shops, and public spaces throughout the city. The town transforms into a kaleidoscope of color, and special events, including parades of girls in kimonos on boats, take place on the canals. It is a deeply moving and visually stunning festival that highlights the community’s love for its children and commitment to preserving tradition.

A Traveler’s Guide to the City of Water

Navigating Yanagawa is refreshingly straightforward, but a bit of planning can make your visit even smoother and more enjoyable.

Access and Orientation

Yanagawa is easiest to reach from Fukuoka City. From Nishitetsu Fukuoka (Tenjin) Station, the Nishitetsu Omuta Line provides direct express trains that reach Nishitetsu Yanagawa Station in about 50 minutes. The journey itself is enjoyable, taking you from Fukuoka’s urban landscape into the flat, green stretches of the Chikugo Plain.

When you arrive at Yanagawa Station, you’ll find ticket counters for various kawakudari boat companies. It’s highly recommended to purchase a combination ticket that includes a one-way boat ride and a bus transfer. Typically, you’ll take a shuttle bus from the station to the boat departure point upstream, and then the 60-70 minute boat tour ends conveniently in the central tourist area near the Ohana villa and its famous eel restaurants. From there, you can explore on foot and later return to the station by local bus or taxi.

Photographer’s Notes

For photographers, Yanagawa is a treasure. The best light occurs during the golden hours of early morning and late afternoon, when the sun casts long shadows and bathes the water in a warm glow. A polarizing filter is essential for reducing glare on the water and enhancing the colors of the sky and foliage. Be ready for the challenge of shooting from a moving boat: a fast shutter speed will freeze the motion of the sendo and capture crisp details of the scenery. Don’t focus solely on sweeping landscapes—seek out small details like the texture of an old wooden wall, a carp swimming below, or the expression on your sendo’s face as they sing. The low bridges offer excellent opportunities for dramatic framing and unique perspectives, so be prepared to shoot quickly as you pass beneath them.

Practical Tips

- Wear comfortable slip-on shoes, as you’ll likely need to remove them when entering restaurants and historical buildings.

- Bring a hat and sunscreen, especially from spring through autumn, since the boat provides limited shade.

- While many smaller restaurants only accept cash, major establishments and ticket counters generally take credit cards. It’s wise to carry some yen just in case.

- The boat tour is one-way, so plan your day to explore the area where the boat drops you off before returning. This spot, known as Okinohata, houses most of the main attractions.

- During peak seasons like spring cherry blossoms or the Sagemon festival, expect crowds. Starting your day early is the best way to avoid the largest tour groups.

The Echo of Water and Smoke

A day in Yanagawa lingers long after you’ve departed. It lives on in the memory of the gentle, hypnotic rocking of the donko-bune. It echoes in the boatman’s song, a melody that seems to rise from the water itself. Most powerfully, it remains in the taste of the seiro-mushi—a profound warmth that feels like an infusion of history, craftsmanship, and place. Yanagawa teaches you to slow down, to observe, to listen, and to savor with intention. It is more than a city of water; it is a city of currents—the currents of the canals, the currents of time, and the rich, flavorful currents of a tradition that steams its story right into its most cherished dish. To visit is to drift away from the modern world and find yourself immersed in a poem you can eat.